Graduate College focuses on translating research into real-world impact

Michele Clark studies invasive plant species, and her research could help save people from being attacked by tigers in a forest in Nepal. Ashley Quay knows that it feels overwhelming to think about how to save the environment, so she used her studies to develop a way to empower people to make small changes.

These women are just two of the hundreds of graduate students at Arizona State University who are taking their research and applying it to the real world. They also were the two winners of the Knowledge Impact Mobilization Awards presented by the Graduate College last week.

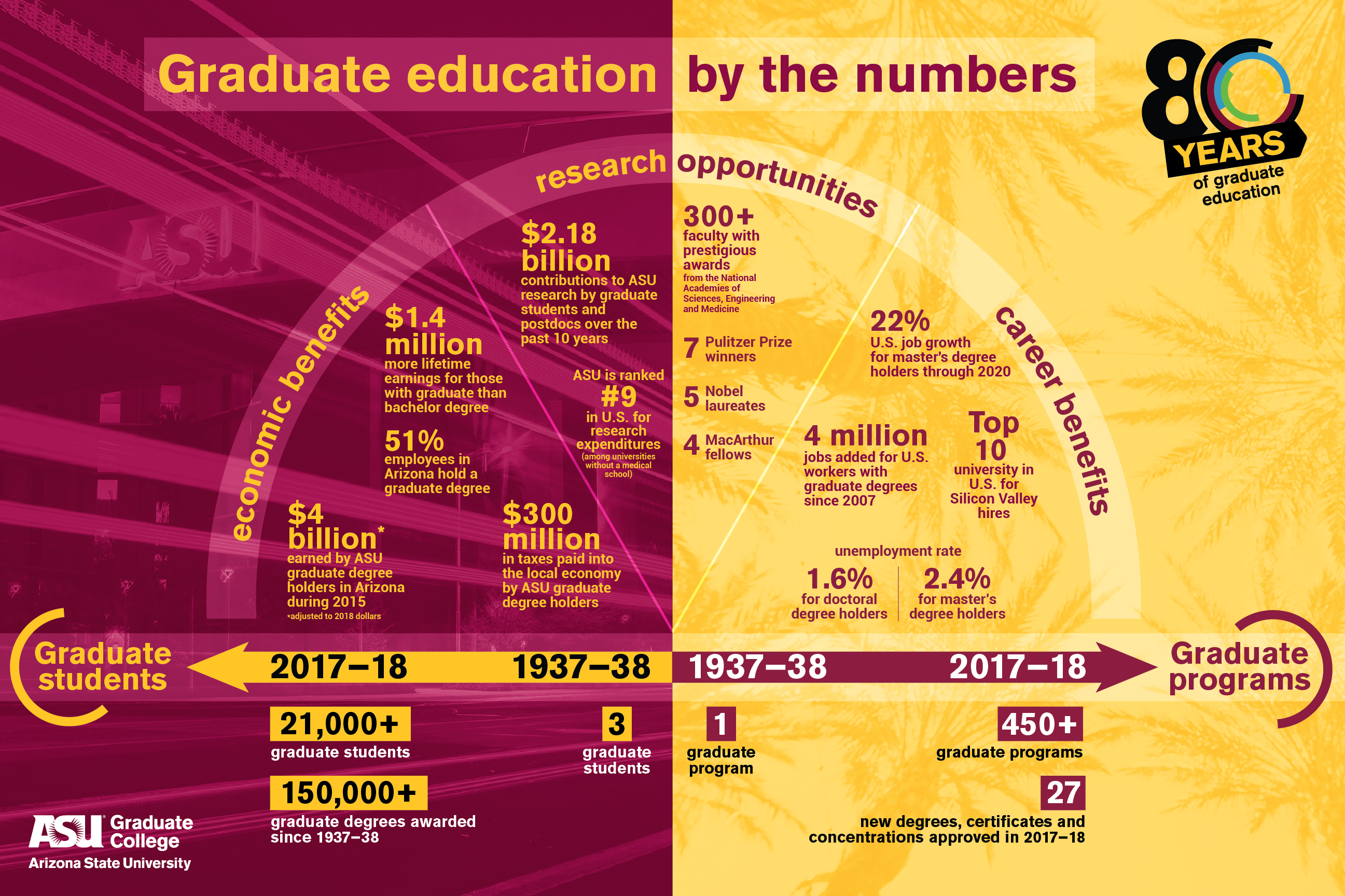

The awards were the latest in a series of events marking the 80th anniversaryThe first head of graduate education was Frederick Irish, namesake of Irish Hall. of graduate education. ASU conferred Master of Arts degrees in education to four students in 1938. In 1958, the Graduate College was officially formed, and the first PhDs were granted in 1963–64. Now, the college serves more than 21,000 graduate students across all locations and online from 125 countries.

And while nodding to its history, the Graduate College is focused on looking ahead, according to Alfredo Artiles, the dean of the Graduate College and the Ryan C. Harris Memorial Professor of Special Education in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College.

“Graduate education is about specializing, going deeper into topics and developing expertise in specific areas. For many years, that specialization was along disciplinary lines,” he said.

But ASU is known for blurring disciplinary lines. And that’s why there are nearly 70 master’s and doctoral programs in interdisciplinary areas such as environmental social science, health care and healing environments, and supply-chain management and engineering.

“It’s not just an advanced degree. You come out of our programs with a mindset, a commitment to engage in problems that matter to people,” Artiles said.

That’s how Clark saw her research in Nepal, where she spent time talking to the villagers whose lives depended on the forest. They helped her design an experiment to remove an invasive vine that was obscuring the forest, making villagers looking for firewood more vulnerable to attacks by tigers and other animals. Then, the community members themselves worked on the project, which was successful.

“By encouraging their perspective, we were able to design an experiment that was culturally and financially feasible to them,” said Clark, a doctoral student in environmental life sciences.

After that, she held workshops and designed an information kit for the villagers to share with other communities in Nepal on how to eradicate the vine.

“Our mission was to make science that is relevant, transparent and useful for the local community to use,” she said.

That “knowledge mobilization” is critical to the mission of the Graduate College, Artiles said at the awards ceremony.

“It’s a very relevant notion. We live in an era of the most incredible knowledge production in the history of humankind. The expectation is to not only produce it and possess it, but to use it for demonstrable impact,” he said.

“And that is the challenge. It’s clear universities have to make greater investments and pay greater attention to the way we prepare researchers. Knowledge mobilization should be at the center of the toolkit our graduates have by the time they finish our programs.”

So two years ago the Graduate College started the Knowledge Impact Studio, a one-credit course to teach grad students how to translate their research into real-world action.

“It’s the ‘so what?’" Artiles said. “We don’t want the knowledge to stay in the journals. We want it to be out and to be used.”

The course walks students through a process in which they answer, “Why do people care about this?"

“We force them to move into the professional arena and the concerns of policymakers,” Artiles said.

The studio helped Emily Zarka turn her dissertation into a series with PBS Digital Studios. The show, called “Monstrum,” streamed on Facebook last fall and will appear on YouTube starting April 10. The series explores monsters and legends from a literary perspective.

“It was an amazing opportunity not only from a networking perspective, but also because the conversations and training I received gave me the confidence to approach PBS and consolidate my ideas and make them as big as they could be,” said Zarka, who received a doctorate in British Romantic literature and is now a faculty associate in the Department of English.

Part of the training involved developing a “pitch.”

“How do you pitch your research like it’s a product to the public?” said Zarka, who presented her project to a roomful of businesspeople during the training.

“We were literally giving our presentation to people who had zero idea of what we were talking about and who were not in our field.

“It’s not something that a lot of academics want to talk about because we have this idealized vision of what we want our research to be.”

A level of personalization

In the early years, graduate education at ASU was intended to train teachers. Tamara Underiner, associate dean for academic affairs at the Graduate College, looked into the history of the college in preparation for the anniversary events, even reading the minutes of the university graduate council from the 1930s. A few years after the first graduate degrees were awarded, someone wanted to do a thesis on a topic other than education. The committee was divided on whether to allow it.

“The minutes reveal in a subtextual way how strongly held these opinions were and how high-stakes they considered it to be,” she said. “We were a teachers’ college back then.”

So the committee took it to the president of ASU at the time, Grady Gammage.

“He took the opinion that it was better to keep an open mind about these things,” she said.

Now there are 525 graduate degrees and certificates offered. Famous graduate alumni include Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, who has a master’s degree in social work; Temple Grandin, an author and speaker on autism and a professor of animal science at Colorado State University, who has a master’s degree in animal science; and Barbara Barrett, a former astronaut, ambassador, presidential adviser and chairman of the Aerospace Corp., who has master’s and law degrees from ASU.

Underiner was a faculty member in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts and said that the Graduate College has always been committed to helping students find funding.

“I was always looking out for scholarships and fellowships that I could help my students apply for when I was a mentor,” she said. “You don’t really expect that level of personalization at a place as big as ASU.”

Sharing best practices

Graduate students earn their degrees from the college of their program, so why have a Graduate College at all?

“One reason is to ensure there is program quality and integrity and that we’re designing and implementing programs that follow best practices and expectations from disciplines and credentialing boards,” Artiles said.

Another reason is to share best practices among the disciplines, like setting up a mentoring program, creating a handbook or recruiting the best candidates.

“We have the benefit of standing above and understanding the different strengths,” he said. “This is critical because we can use experiences in one part of the system to be a model in another area.”

The Graduate College also provides mentoring for students, support and resources for postdoctoral researchers and added staff to help students get their research nominated for prestigious awards.

Ashley Quay, who is pursuing a master's degree in sustainability leadership, is congratulated by Graduate College Dean Alfredo Artiles after she won the Knowledge Mobilization Impact Award. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

The Knowledge Mobilization Awards program also is relatively new, in just its second year. While Clark won the award for doctoral students, Quay won for master’s degree students. She is pursuing a master’s degree in sustainability leadership.

Her project, “Positively Impactful,” is a social-media campaign and website that highlights changes people are making to be more sustainable.

“The doom-and-gloom approach is leaving people disheartened, overwhelmed and stagnant to change,” Quay said.

“But through my studies, I realize people are taking concrete steps, and now I feel hopeful and empowered that I can create change.”

The Graduate College Distinguished Lecture will be held at 4 p.m. April 16. William F. Tate IV, the dean of the Graduate School and the vice provost for graduate education at Washington University, will give a talk titled, "Disrupted! Graduate Education and the Democratic Project."

Top photo: Michele Clark, who is pursuing a doctorate in environmental life sciences, gets a congratulatory hug after winning the Knowledge Mobilization Impact Award for her project, "A Toolkit for Fighting Invasive Plant Species in Nepal." Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now