On Thursday night, explorers gave a first report of a new land.

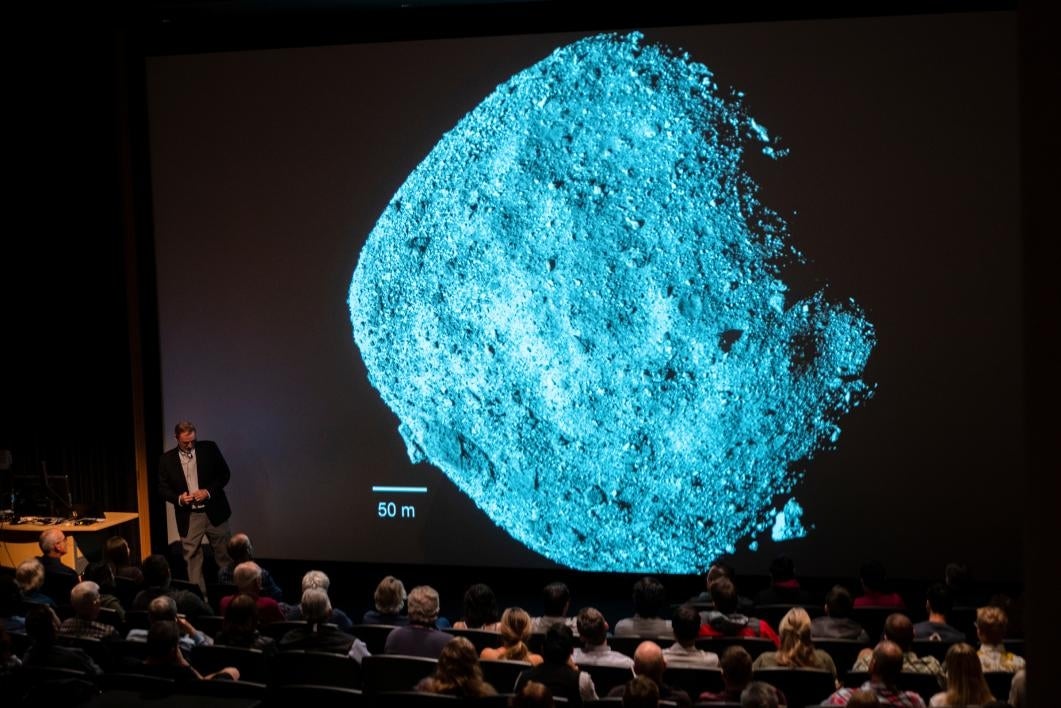

A packed house at Arizona State University heard the first details of the mission to study an asteroid beyond Mars.

After a two-year voyage, the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission arrived at Bennu, an asteroid the size of the pyramid at Giza, in December.

And it has surprised scientists since.

“We didn’t know what it looked like, and that’s called exploration,” said Phil Christensen, mission co-investigator, lead of the spacecraft’s OTES instrument, and Regents' Professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at ASU.

First surprise: Bennu is a craggy ball, with some boulders the size of houses. Scientists thought taking the sample return was going to be like plucking something from a football field. It’s not.

“It’s going to be like landing between two parked cars in a parking lot,” Christensen said.

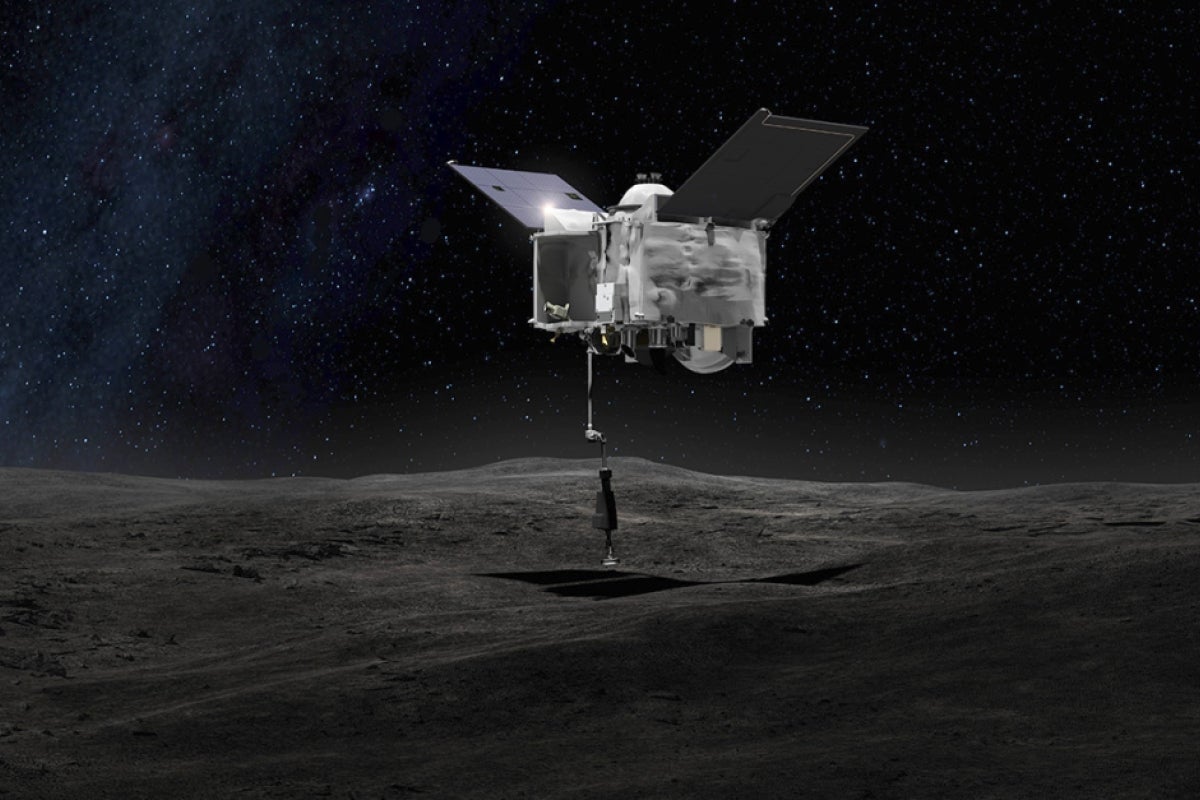

That problem is a ways off. The asteroid will be studied for a year before the craft touches down — briefly — on the surface and grabs four pounds of material, which will be sent back to Earth to crash into the Utah desert in 2023.

“The beauty of this mission is … we get to bring rocks back,” Christensen said.

Operating the spacecraft is breaking records — for orbiting a body this small, and for orbiting so closely. The spacecraft is flying above the asteroid at the height of the Empire State Building.

“The navigation on this mission is amazing,” Christensen said.

Bennu holds water.

“What’s interesting about these meteorites is that they contain water,” said Vicky Hamilton, a co-investigator on the OSIRIS-REx mission, lead for the OTES spectrum analysis team and a planetary geologist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

It’s not in liquid form, but it's in the minerals — up to 2 percent in some cases. Bennu’s parent body had significant interactions with water, Hamilton said.

Much more data will be collected over the next calendar year.

Scientists think asteroids may contain clues to the origins of life. The small, rocky bodies have never been explored before. No one knows how they form, how they behave or what’s on them.

The samples will be studied by scientists for decades.

“Literally, the carbon that’s on Earth came from asteroids like Bennu,” Christensen said.

Bennu is not a solid rock. It’s either porous or formed of a very “fluffy” — Christensen’s word — material.

This type of meteorite is so fragile, if you get it wet or touch it with your hands, it’s ruined, said Devin Schrader, a carbonaceous meteorite collaborator on the OSIRIS-REx mission. He is also an assistant research professor with the ASU Center for Meteorite Studies.

One of the reasons Bennu was chosen for exploration is its relatively high likelihood of hitting Earth in the next century. Knowing the physical and chemical makeup of the asteroid will be critical to know in the event of what NASA calls an “impact-mitigation mission.”

OTES stands for OSIRIS-REx Thermal Emission Spectrometer. It will sniff out what types of minerals are on the asteroid, how big the particle sizes are and what the temperature is. It has been vital in the year of mapping and studying Bennu before the decisions are made on where to pick up samples, and it’s the first space instrument built entirely on the ASU campus.

Top photo: This mosaic image of asteroid Bennu is composed of 12 PolyCam images collected on Dec. 2 by the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft from a range of 15 miles (24 km). The image was obtained at a 50-degree phase angle between the spacecraft, asteroid and the sun, and in it, Bennu spans approximately 1,500 pixels in the camera’s field of view. Image by NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great cybersecurity hacking competition.And experts at Arizona State…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…