Bringing back extinct species: If we can, should we?

A Tasmanian tiger (thylacine) at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, Tasmania, 1928. The species went extinct in 1936. It was the target of a Tasmanian government bounty aimed at protecting a precarious sheep industry on the island. However, bad livestock management was the real culprit behind the sheep farmers’ troubles. Public domain photo

Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. Read more top stories from 2019.

Poachers are still making headlines as the demand for rhinos, elephants, tigers and other endangered animals remains strong. Climate change is taking a heavy toll on many animal, insect and plant species around the world. And the human impact on natural habitats including oceans, rainforests and desert lands is worsening.

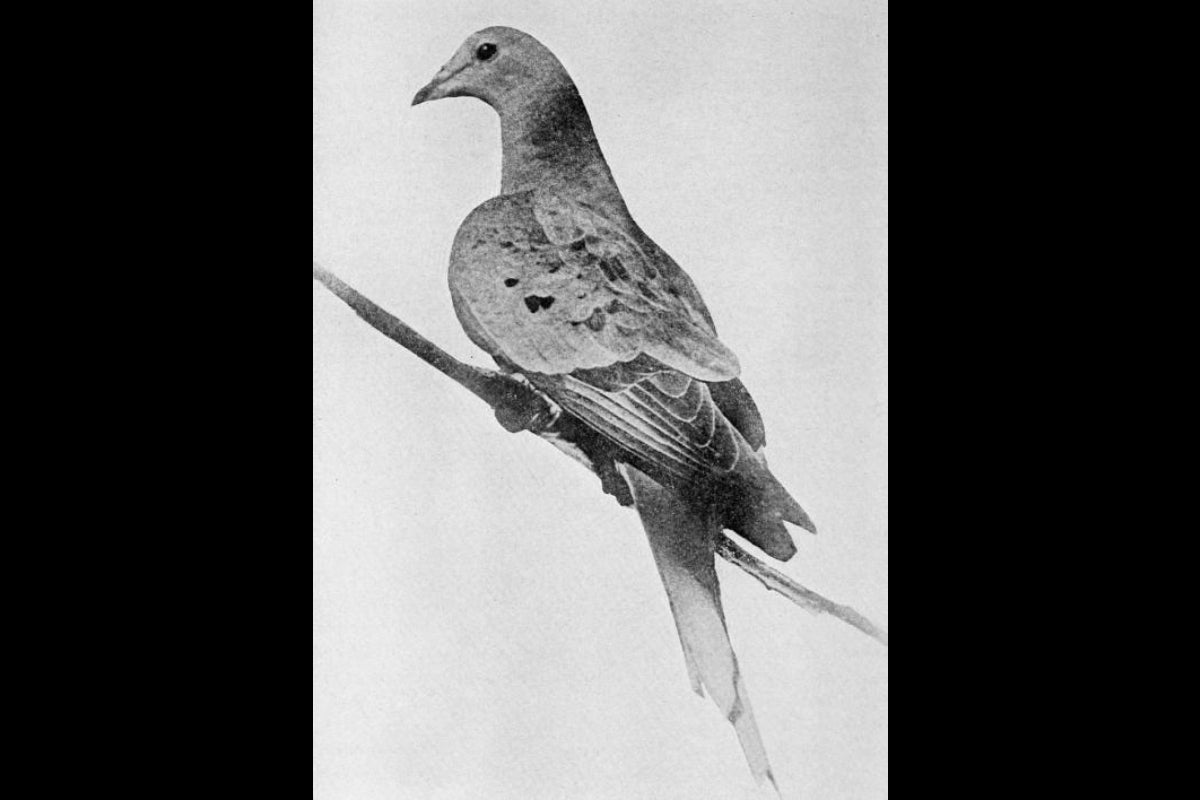

With troubling news such as this, one might think that animal extinction caused by humans is a more recent phenomenon. But history shows us otherwise. The passenger pigeon, Tasmanian tiger, northern white rhino, Zanzibar leopard and Pyrenean ibex are just a few examples of species that have gone extinct in about the last 100 years because of humans.

The losses of animals like these have spurred some conservationists to do just about anything to save other endangered animals and have inspired researchers to develop technology that might bring back once-extinct species.

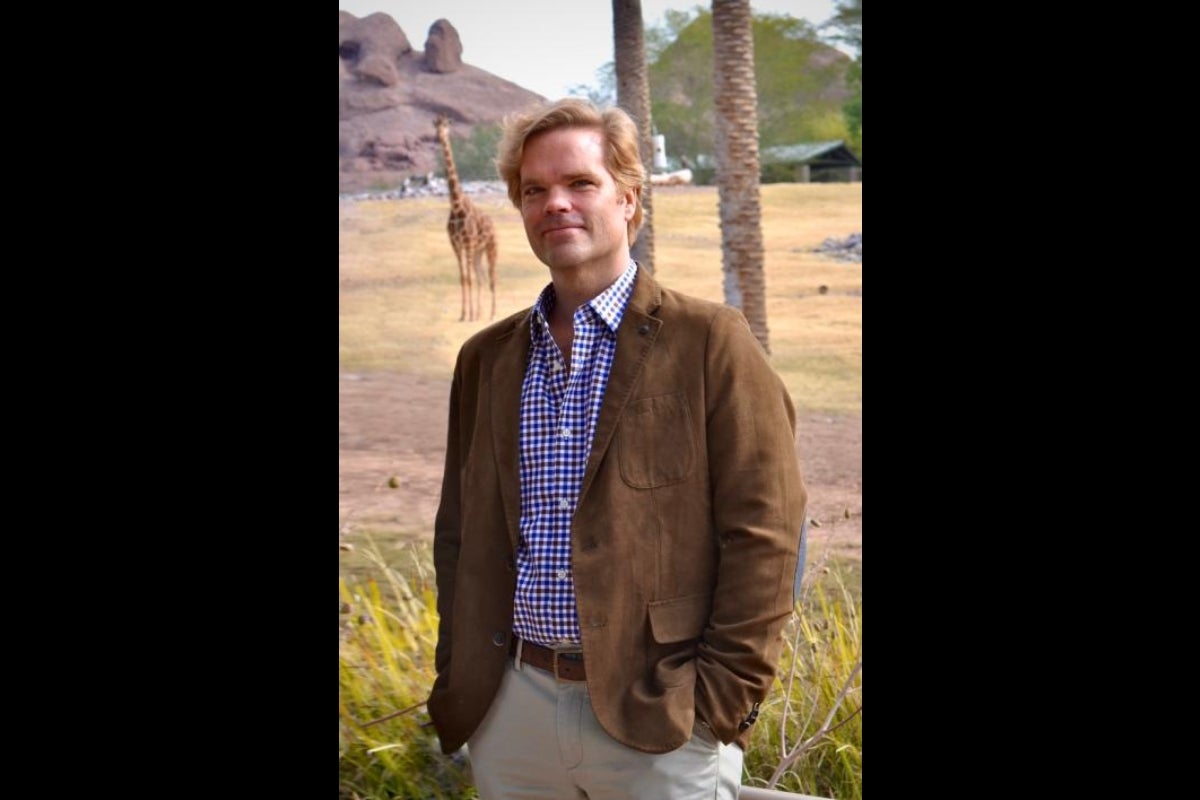

In his new book, “The Fall of the Wild: Extinction, De-Extinction, and the Ethics of Conservation,” Arizona State University’s Ben Minteer looks into the ethical dilemmas of the loss and recovery of animal species.

“A few years ago, I began to notice that my writing about extinction and the wild was becoming preoccupied with the challenge of balancing the pragmatic need for action with a respect for more traditional preservationist values,” said Minteer, a professor with the School of Life Sciences and the Arizona Zoological Society Endowed Chair at ASU. “The science editor at Columbia University Press approached me about putting together a little book on the subject. He’d read some of my writing on de-extinction and specimen collection and thought these views could be presented to a broad audience.”

In a conversation with Minteer about “The Fall of The Wild,” he discussed the ethical issues surrounding the possibility of bringing back extinct species, such as the Tasmanian tiger, as well as the erosion of the wild as a moral ideal.

Question: Around the world, animals, plants and insects are dramatically declining in numbers and may go extinct. In fact, many people believe we are experiencing a sixth mass-extinction event. Some scientists say “de-extinction technology” could be used to bring back extinct species. Yet this would not change human behavior, which likely caused the problem in the first place. Could you discuss?

Answer: Well, as I write in the book, I don’t think we would really be bringing back extinct species such as the Tasmanian tiger or the passenger pigeon. We may eventually be able to create facsimiles of these animals through genetic tinkering, but to my mind, they’ll be new species, animals de-coupled from the natural history of the original forms. Still, you raise an important point, and it’s one of the main themes of “The Fall of the Wild.” There’s a sense in which these “fixes” elide the hard questions and deeper lessons of extinction, which are more wrapped up in our environmental values and lifestyles than in a technical exercise in gene editing.

Q: In the book, you discuss an “authentic ecological conscience.” What do you mean?

A: I borrowed this from the great conservationist-philosopher Aldo Leopold, who observed that moral obligations have no meaning without the compulsion to do the right thing even when no one is looking. It’s a quaint expression, but it captures a powerful idea about moral responsibility. Leopold’s notion of an ecological conscience serves as a touchstone in my book, helping me understand why, for example, the collection of specimens from newly discovered or re-discovered species may be risky — or why conservation efforts to relocate species in advance of climate change are insufficient if they don’t address larger ecological and social maladies.

Q: What about the issue of unintended consequences? There are many examples in science where an invention or new technology was initially wonderful, but then unexpected issues became new problems.

A: It’s an anxiety that runs through “The Fall of the Wild,” though the unintended consequences I’m most concerned with have to do with our environmental character. Will we be able to maintain respect for a wild nature that we are increasingly manipulating, controlling, even attempting to re-create via genetic engineering? So, the “fall” I’m worried about is really twofold: the loss of wild species and places in the human age, certainly, but also the fading of the wild as an ethical ideal.

Q: But what does “wild” mean any longer? Are there any spaces on Earth that are actually untouched by humans and human activity?

A: I think it’s a matter of degree. Although it’s true that the human fingerprint is visible even in the most remote corners of the planet as a result of anthropogenic climate change, many places and animal populations remain largely uncontrolled and therefore wild in the traditional sense. And of course, wildness can also be found closer to home, including in the midst of cities and subdivisions. Even Leopold, one of our greatest champions of the wild, understood that it was a relative idea, a quality you could find at the edge of a cornfield if you looked closely enough.

Q: What is going right with conservation? If one reads regularly about conservation, the news is grim. Are there positive changes happening that we can look to for hope and optimism?

A: Plenty of things are going right! And success stories are everywhere, from endangered species pulled back from the brink, to river restoration projects, to ranchers and conservationists working together to mitigate rural sprawl. It’s important to be aware of the challenges, but we also need those stories of hope. I always like to remind my students that you don’t have to take on everything at once — that’s impossible! Find a conservation issue or concern that matters to you, learn all you can about it, and then see how you might make a difference.

Q: You talk in the book about the techno-environmentalist Stewart Brand’s idea that “We are as gods and we have to get good at it.” You respond with a call for “an ethic of collective self-control and ecological restraint.” Could you expand on this idea?

A: Brand and I see this very differently. He’s pushing us to use our technological acumen to revive extinct species and take hold of the ecological and evolutionary reins, to unleash our power for environmental ends. I’m deeply concerned about that power and wary of spurring it even harder, especially in nature conservation. As I write in the book, I think true power resides not in greater control of nature, but in acts of forbearance, especially when our interventions may undermine other environmental values that we care about. I have great respect for Brand, but I just think he’s wrong about this.

Q: What are the two or three main takeaways from “The Fall of the Wild”?

A: Our efforts to conserve, recover and restore species are rightly celebrated as some of the best episodes in our environmental history. At the same time, we’ve shown that we’re capable of going too far in these efforts, especially when the siren call of new technologies and the urgency of global threats such as climate change start to grip us. My book is an attempt to push back against those impulses and remind us of the fallout of these more aggressive pursuits on our environmental ethics.

Q: In the past few years, you’ve published multiple books and articles related to conservation, extinction, the wild, zoos and more. Since you’ve become the Arizona Zoological Society Endowed Chair, what are some of the things you’ve learned? And what’s next?

A: Too many things to list that I’ve learned along the way — and always more to understand. But the vantage point of the chair position has allowed me to get a better handle on the complexities of animal conservation and a clearer view of how it works across institutions.

I’m starting a new project that explores the idea of the wild in zoos and wildlife parks, what it means and how we might enhance it. The book will be a collaborative effort with the distinguished biologist Harry Greene, a good friend and also a sparring partner for many of the issues I tackle in the book. Harry and I probably agree about 90 percent of the time on conservation questions, but de-extinction is definitely part of the other 10 percent! I’m excited about this one.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…