With the arrival of the holiday season, you’ve likely been bombarded with customized coupons and gift recommendations designed to steer you to products and services you’re most inclined to buy. Retailers and free service providers like Facebook and Google reap revenue with these highly curated and targeted advertisements — but at the cost of your data.

The recent increase in consumer privacy violations motivated Arizona State University Associate Professor Lalitha Sankar to develop game theoretic models that retailers and service providers can use to help them generate accurate recommendations while guaranteeing consumer privacy.

“Recommendation systems are everywhere,” said Sankar, an electrical engineer in the faculty of ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering. “How can these systems make recommendations without knowing who you are? Should they know your political preferences? I think some of it is inevitable, but where should we draw the line?”

Every time you shop, you reveal data about your purchasing behaviors. Whenever you use a free service, you implicitly consent to having your data collected, stored, sold and shared. The information gathered paints a picture about what you like, what you dislike, what you may need and which coupons, services or products are most likely to make you happy.

Understanding retailer and consumer interactions in the context of privacy

When a retailer automatically tracks a consumer’s financial transactions, purchasing behavior and preferences, it makes it easier to offer customized incentives. But sometimes these incentives imply the retailer has learned sensitive or private information about the consumer.

Such was the case six years ago when Target figured out a young woman was pregnant and began sending pregnancy-related coupons to her home address, which were intercepted by her father before she ever got a chance to share the news.

By identifying and analyzing consumers’ prior purchases of specific products, Target is able to send customized advertisements, such as coupons, based on very specific stages of a woman’s pregnancy. But in some cases, like the one mentioned above, personalized marketing tactics are impacting consumers’ lives beyond the shopping aisle.

“These privacy violations are making consumers very wary about purchasing products from such retailers,” Sankar said. “So, how can retailers over the long-term maximize their profit without creeping out consumers?”

Sankar and her then-doctoral student Chong Huang, who is now a postdoctoral research associate in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, one of the Fulton Schools, along with Anand Sarwate, an assistant professor at Rutgers University, proposed a mathematical framework for modeling decision-making so retailers can develop coupon-offering policies that earn revenue while being sensitive to consumer privacy concerns.

The framework builds on a well-known model for nondeterministic systems called partially observed Markov decision processes, which allows modeling of the fact that retailers don’t know how a consumer may react to a targeted coupon (for example, feeling creeped out or accepting it happily) but can learn and improve their understanding of consumers from information about numerous interactions.

Thus, retailers can learn not only what consumers may be interested in but can also potentially estimate the privacy sensitivity of a consumer.

While some effort will be needed to put this theory into practice, the work could enable retailers and free service providers, such as Facebook, to use consumers’ responses — to sponsored ads, for example — to better learn and respect consumer privacy sensitivities.

Privacy consequences of using free online services

Sankar and Huang have also been researching the impact of privacy on free online service markets, such as social media, search engines and mobile applications. These online interactions between consumers and service providers have steadily increased due to advances in technology.

While consumers enjoy the benefits of free services and customized recommendations, privacy violations are occurring more frequently as providers use private information for targeted ads.

“Today, machine-learning algorithms and designers have to be cognizant when taking data from a variety of entities about whether they are violating individual privacy or inferring information they shouldn’t be inferring,” Sankar said. “This is happening all the time, but there should be some degree of privacy guarantees.”

Service providers like Google and Facebook are often able to gather such tailored information about their users because of their search queries. So, the research team began asking the broader question: What if there was competition to free service providers such as Google and Facebook?

Would consumers prefer a competitor that offers less targeted advertisements and search results if they could guarantee more privacy because they’re not collecting as much user data? The competitor wouldn’t target ads at users based on their personal information the way these data giants do.

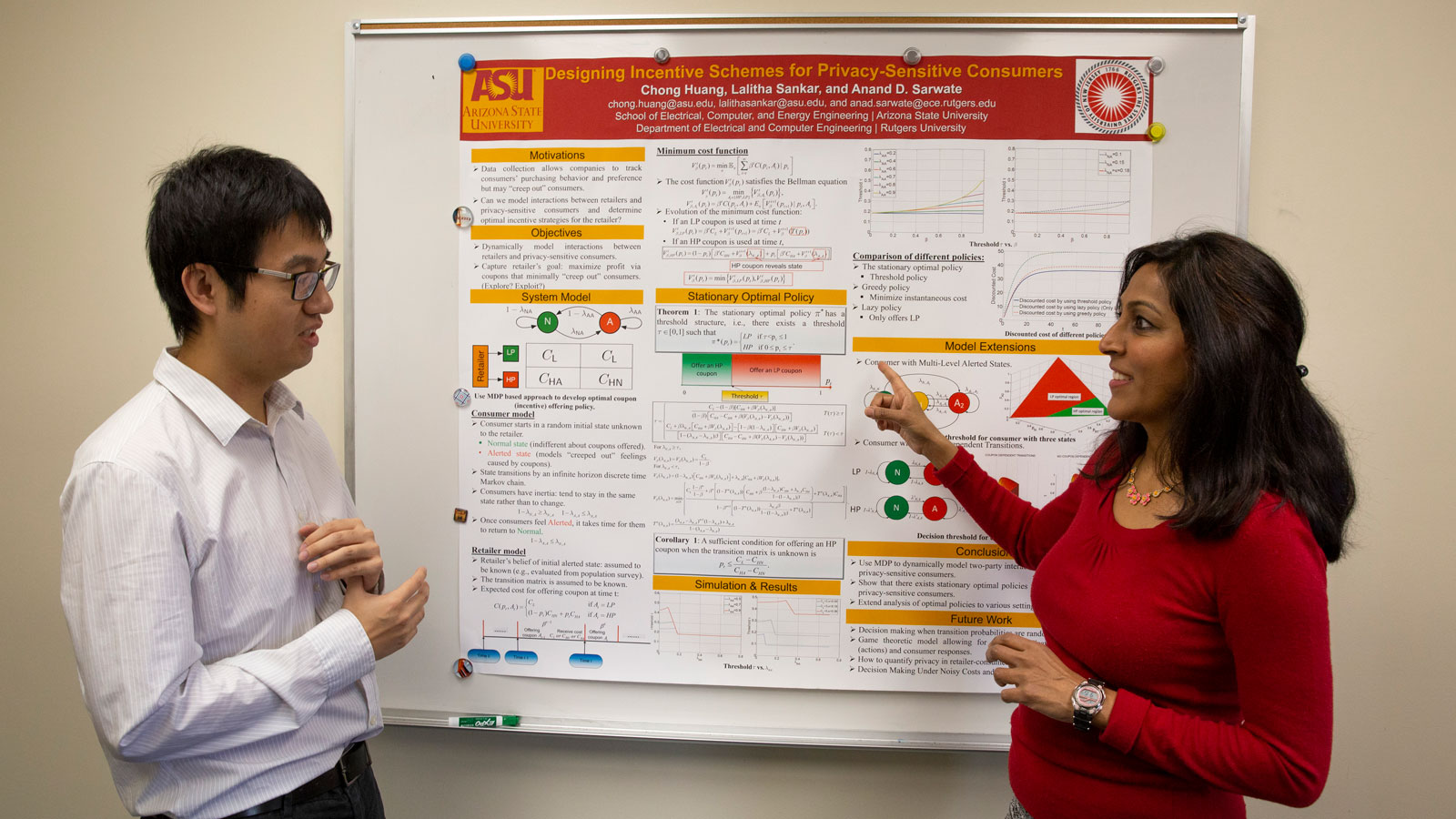

Associate Professor Lalitha Sankar (right) and former doctoral student Chong Huang, now a postdoctoral research associate in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, have been researching the impact of privacy on free online service markets to determine if privacy-differentiated services can lead to a sustainable marketplace. Photo by Erika Gronek/ASU

Sankar and Huang propose a game-theoretic approach to identify if privacy-differentiated free online services can lead to a sustainable marketplace and a meaningful market share for service providers that offer privacy guarantees.

The free online search engines Google and DuckDuckGo offer a study in contrast to the enterprise model on privacy policies. Google’s profit is based on enabling targeted ads to reach consumers that use its search engine while DuckDuckGo appears to be preferred by highly privacy-conscious consumers attracted by its no targeting guarantees, Sankar said. Yet, the latter has a very limited market share and this leads to the question of how much consumers are willing to forgo quality of service for privacy protection.

Sankar and Huang have built upon a classical model in market economics called the Hotelling model to determine how enterprises offering similar goods can differentiate themselves and yet be profitable by capturing sufficient market share.

In the context of free online services, since price is not a differentiator, Sankar and Huang have developed simple yet realistic cost and revenue models that highlight the effect of a service’s market share of a variety of factors, including heterogeneity of consumer base, differentiated revenue sources, consumer evaluation of privacy risk and consumer desire for service quality.

The research on the impact of privacy on free online service markets was recently accepted at GameSec, a prestigious conference on decision and game theory for security.

“These very new problems will become big problems,” Sankar said. “Maybe no one cares about recommendation systems from Netflix. But what if an enterprise has your DNA information? What if it uses it to recommend insurance policies, medical treatment or even leads to a denial of insurance coverage? Privacy is eventually going to become a big problem in the context of medical data and a variety of very personal data.”

Privacy awareness for middle and high school students

Sankar recognizes that privacy concerns may be less worrisome to a younger generation of online users who have grown up with the internet inextricably woven into their daily lives.

She has partnered with Catherine Wyman, a computer science teacher at Xavier College Preparatory, to host outreach events at the all-female private high school in Phoenix. The events focus on the social implications of not having good privacy settings on social media sites, such as Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat.

Sankar enlists the help of ASU undergraduate students in science, technology, engineering and mathematics disciplines, many of whom also graduated from Xavier College Preparatory, to assist with the discussions, hands-on demos and interactions with the young girls.

Using characters from popular movies, such as "Harry Potter" and the "Minions," young girls can grasp the importance of how privacy settings should be set up to ensure private information doesn’t get shared with unknown recipients. More recently, Sankar and her undergraduate students talked about location privacy and how geo-tagging can be dangerous.

“It’s important for girls to know how to set up their privacy settings,” said Sankar, “especially now with the onset of cyberbullying. This age group is much more likely to be affected.”

Sankar and her undergraduate students are working to bring the outreach event to ASU’s Open Door event in the hope of reaching a broader audience in the local community.

Top photo: Lalitha Sankar, an associate professor of electrical engineering in Arizona State University’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, has been researching game theoretic models. Photo by Erika Gronek/ASU

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…