Shocking announcement of world’s 1st gene-edited babies ushers in brave new world

Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. Read more top stories from 2018 here.

A new era for humanity has unexpectedly arrived in the form of gene-edited twins.

On the eve of the second International Summit on Human Gene Editing in Hong Kong, a bombshell was dropped with a startling series of YouTube videos published on Nov. 25 by a scientist who had clearly gone rogue.

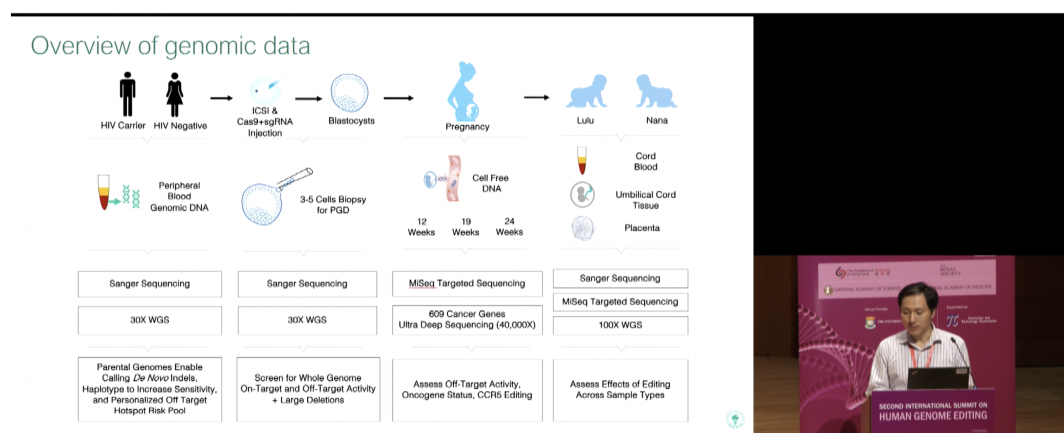

In the videos, Chinese researcher He Jiankui announced the births of the world’s first gene-edited babies — twin girls named Lulu and Nana — who had their genomes permanently altered in the hopes of giving them lifetime protection against HIV infection.

Any such gene-editing work on human embryos has been expressly forbidden by a consensus reached by leaders in the field after the first gene-editing summit, held in 2015, and subsequent guidelines issued by the National Academy of Sciences in 2017.

But the guidelines, despite the efforts of well-meaning scientists, are just guidelines and can be ignored since there are no formal international laws in place to prevent such work.

It was known that He had been working on gene editing, but the pregnancies were a complete secret. Apparently, He used part of his own money to make gene-edited babies, without knowledge from the scientific community or even his own institution, the Southern University of Science and Technology in the fast-growing high-tech corridor of Shenzhen, China.

The scientific community quickly condemned the researcher's actions. The chair of the organizing committee, Nobel laureate David Baltimore, called He’s actions “irresponsible" and “a failure of self-regulation by the scientific community.”

Many scientists questioned whether the gene editing was medically necessary.

Speakers at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing have been mobbed all week by the press, asking for commentary as they learned of He’s actions.

Among the attendees was Arizona State University School of Life Sciences science historian and bioethicist J. Benjamin Hurlbut. Back in March, Hurlbut helped spearhead an effort to try to spark a new kind of international, “bigger” conversation on gene editing.

Hurlbut presciently wrote in Nature, along with Harvard collaborator Sheila Jasanoff: “Unless these [genome] editorial aspirations are more inclusively debated, well-intentioned research could move humanity closer to a future it has not assented to and might not want.”

After learning firsthand of the details of the CRISPR babies, Hurlbut told Chemical & Engineering News in an interview at the summit that He’s purported achievement “simply leapfrogs completely over anything that would count as treatment into something that is much more unequivocally in the territory of enhancement.”

The timing of the designer baby news — first reported by MIT Technology Review and later, by the Associated Press (which was allowed advance access to film in He’s lab as part of its exclusive) — was also highly unusual because it had not been presented at a scientific conference or published in a peer-reviewed journal.

READ: Hurlbut and colleagues' editorial piece on who is to blame

So, when He appeared during his prior-scheduled summit presentation spot on Wednesday, there were crowds lined up hours ahead of time, with reporters and photographers flanking the aisles to hear the first details of his clinical trial.

The room was “packed with reporters, the racket of cameras clicking away like mad, a huge crowd,” said Hurlbut. “He’s presentation was thorough and calm. He was questioned by Mathew Porteus and Robin Lovell Badge, two leading scientists, who did an extraordinary job of managing the crowd and conducting a calm, thoughtful and thorough discussion. He was remarkably collected under the pressure of it, particularly given that he is, in my experience, a somewhat soft-spoken and rather shy person. Many questions focused on his motivations, which he answered thoughtfully. Other questions focused on the ethical review process. He answered vaguely or incompletely.”

According to Baltimore, there were upwards of 1.8 million people watching the summit livestream of (He's talk begins about the 1-hour, 18-minute mark), which played out late at night back in the U.S.

“It was a very unusual scene for a scientific meeting, and yet there was no disorderliness from the crowd,” said Hurlbut. “All in all, it was quite calm, professional and appropriate to an august scientific meeting.”

During his presentation, He defended his actions, saying that he wanted to rid the world of HIV infection, “where HIV remains a top-10 cause of death in several countries, in particular developing countries.” He added, “for unaffected children, born to HIV-positive mothers, make up a large percentage of births in South Africa.”

He induced a targeted deletion of a short section of DNA to inactivate the CCR5 gene, which is involved in HIV infection, by using a gene-editing tool called CRISPR-Cas9. CRISPR introduced a new mutant version of the CCR5 gene, one that, according to He, is “a natural protection against HIV carried by as much as 10 percent of the population in several European countries. It prevents HIV infection.”

It is thought that by inducing the mutation in CCR5, HIV cannot enter a cell, thwarting the infection.

Chinese scientist He Jiankui provides the first details of his study at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing in Hong Kong on Wednesday. During his presentation, He defended his actions, saying that he wanted to rid the world of HIV infection, “where HIV remains a top-10 cause of death in several countries, in particular developing countries." Image courtesy of summit livestream from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine

In all, eight couples enrolled for the study and one dropped out, He said.

The babies were made by standard in vitro fertilization methods — with one crucial addition. At the same time a single sperm was introduced to fertilize the egg, the CRISPR gene-editing system with the replacement version of the CCR5 gene was injected at the same time.

In each case, the father was HIV-positive and the mother was not. A total of 31 embryos were injected, He said, and 70 percent were CRISPR-edited with the HIV-resistant version of CCR5.

Two of those embryos were implanted into a woman, who gave birth to twin girls a few weeks ago. They are healthy and being monitored, while the identity of the babies, mother and father are being protected.

“He opted to work on HIV not because there is a heightened medical risk to these children, but because of the social stigma that the disease carries in China,” Hurlbut told CNN. “So the first instance of human germline modification was not only medically unnecessary and a genetic enhancement, it was also undertaken as a genetic fix to a social problem. That is a very dangerous door to open.”

During the Chemical & Engineering News interview, Hurlbut said, “These two lives are now an experiment, a matter of scientific curiosity, which is an outrageous way to relate to human lives.”

During the Q&A portion of the discussion, He, when pressed, seemed to only reluctantly reveal another bombshell — that a second mother is early in her pregnancy with a CCR5, CRISPR-edited baby.

In 2017, during He’s postdoctoral training and visits to America, both Hurlbut and his father, William, a bioethics professor at Stanford, met him at gene-editing meetings. They had the opportunity to discuss CRISPR ethics, exchange emails and help with surveys that He wanted to develop to explore Chinese attitudes toward genome editing.

They described the conversations to STAT news, which Sharon Begley characterized as “the Hurlbuts have discussed the ethics of human-genome editing with He more than any other scholars in the West and probably the world.”

“Clearly he recognized that his work would be controversial,” J. Benjamin Hurlbut told STAT by email. “But for all the unease and even outright condemnation from his scientific colleagues, his actions reflect, at least in part, motivations that are widespread in the conduct of science. His research pushes the envelope, seeks to have a significant impact and aims to make headlines and earn recognition.”

ASU School of Life Sciences bioethicist J. Benjamin Hurlbut gave a talk at the summit Thursday. Back in March, Hurlbut helped spearhead an effort to try to spark a new kind of international, “bigger” conversation on gene editing: "My view is that categorically this should not have been done. Because what was at stake in this project was a matter that belongs to the whole human community.” Photo Courtesy of Peter Mills/Nuffield Council on Bioethics

During his summit discussion on “Identifying Basic Principles for Moving Forward” on Thursday, Hurlbut offered a long-view societal perspective to address the safety, risks and ethics and responsibility of He’s actions, and gene-editing science.

He talked about an event 40 years ago, with the birth of the world’s first test-tube baby, Louise Brown.

“It’s worth remembering that this is not the first time that a risky and controversial experiment in human reproductive technology has been undertaken without thorough preclinical research, has been revealed first through the popular press and without passing through scientific peer review,” said Hurlbut.

“That famous first goes to the inventors of IVF itself (Robert Edwards and Patrick Steptoe). Let’s remember too that rushing into these risky kinds of human applications was not a one-off but is, in fact, a pattern.”

WATCH: Summit's archived webcast — Hurlbut's talk starts around the 2-hour, 3-minute mark

There was the 2000s political and ethical controversy over human embryonic stem-cell science, and Hurlbut mentioned the more recent development of “three-parent” babies to treat infertility.

“Professional self-regulation often fails to hold these in check, particular in a scientific culture that rewards provocative research, grabbing headlines and famous firsts,” said Hurlbut.

“We should seek to learn from the event of this week because it kind of continues a larger pattern rather than departs from it. And it’s a pattern that the wider community has to acknowledge, and own and address.”

“To be absolutely clear, my point is not to justify the experiment that was revealed this week. My view is that categorically this should not have been done. Because what was at stake in this project was a matter that belongs to the whole human community.”

Just how, when and if the international human community can put the genome-editing genie back in the bottle remains to be determined.

Top photo: Researchers and media crowd this week's second International Summit on Human Gene Editing in Hong Kong. Photo by J. Benjamin Hurlbut/ASU

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…