The healing power of pursuing a dream

When Billy Mills beat the pack on a muddy cinder track in the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo, it was one of the greatest upsets in sports history.

The grainy black-and-white video shows his graceful, effortless stride in the 10,000-meter race. But those steps were part of a difficult journey that left Mills, an Oglala Lakota, so despondent that he almost killed himself before he won the gold medal.

“That moment was magical to me. I felt as if I had wings on my feet,” Mills told a crowd at Arizona State University on Thursday night. He spoke at an event titled “Indigenous Identity and the Athletic Experience with Billy Mills,” sponsored by the Alliance of Indigenous Peoples, the Global Sport Institute and the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy. The talk was held at the Tempe campus, which is on the homeland of the Akimel O’odham and Pee-Posh peoples.

Mills was raised on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. When he was 8, his mother died, and his father told him, “It takes a dream to heal broken souls. The pursuit of a dream will heal you.”

“He told me to take our culture, our traditions and spirituality and extract from them the virtues and values that empower them,” Mills said.

His father died when he was 12, but Mills found his passion in running and won an athletic scholarship to the University of Kansas.

“I was not ready for the lack of understanding that Americans had for me,” he said.

He was told he could not join a fraternity or be roommates with his white and black friends. And when he was named an NCAA All-American cross-country runner, he was told to not appear in the official photograph.

“By then I knew something inside of me was broken, but I didn’t know what. I was locked out of the American dream.”

He opened the window of his fourth-floor hotel room and looked down, but heard his father’s voice telling him not to jump.

Then he met Patricia, to whom he has been married for 56 years.

“Instantly, I’m in love,” he said. “Now I have a partner.”

Mills earned a degree, took a commission in the Marine Corps and made the U.S. Olympic team.

At the race in Tokyo, Mills knew he was running a scorching pace, but didn’t think he could keep it up. He felt his blood sugar plummeting, his vision blurring. Also, he was in fourth place. Then he stumbled. He briefly thought of quitting, until he saw Patricia in the crowd.

“She was crying because I was pursuing a dream and she was my support team. I was pursuing a dream to keep from thinking of suicide again,” he said.

“She knew I was taking the virtues and the values of my culture, my traditions, my spiritualty and I was putting them into my Olympic pursuit and my marriage.”

He surged to the finish and was briefly confused when he won.

“Did I miscount the laps? Do I have one more lap to go?”

When Mills returned to the United States, the country was in the midst of civil rights protests.

“The games inspired me to go on a journey into my past to understand footprints laid by my indigenous ancestors and my European ancestors, and what I found is what we face today in America,” he said.

He visited the black church in Birmingham, Alabama, where four little girls were killed by a bomb, and he studied the history of oppression against people of color, up to the “war on drugs” that fueled the growth of gangs on reservations.

He decried the backlash against former NFL player Colin Kaepernick, who kneeled during the national anthem to protest police brutality against African-Americans. Mills said that as a veteran, he supported the protest.

“He’s not disrespecting me. It’s a cry for unity,” he said.

The event also featured Amanda Blackhorse, a Navajo and a social worker who was the lead plaintiff in the lawsuit that sought to revoke trademark protection of the term "Washington Redskins,” a slur against Native Americans. She said she was thrust into the world of sports when she took on the mascot issue.

“I didn’t grow up saying, ‘Someday, I’m going to take the Washington NFL team to court,’” she said.

“A lot of times in social justice and activism, the issues just happen. We don’t seek them. They come to us.”

Blackhorse said she has always admired athletes who take a stand on political issues.

“I was delighted to hear that Billy Mills spoke out against the name of the Washington team. I thought, ‘Yes, an icon is on our side.'"

In 1986, Mills founded the nonprofit group Running Strong for American Indian Youth, and he travels more than 300 days a year, speaking to young people about healthy lifestyles and taking pride in their heritage. Now 80 years old, he said the United States is in “strange times,” but he’s optimistic.

“I know we can come together and complete the maturity of our democracy,” he said.

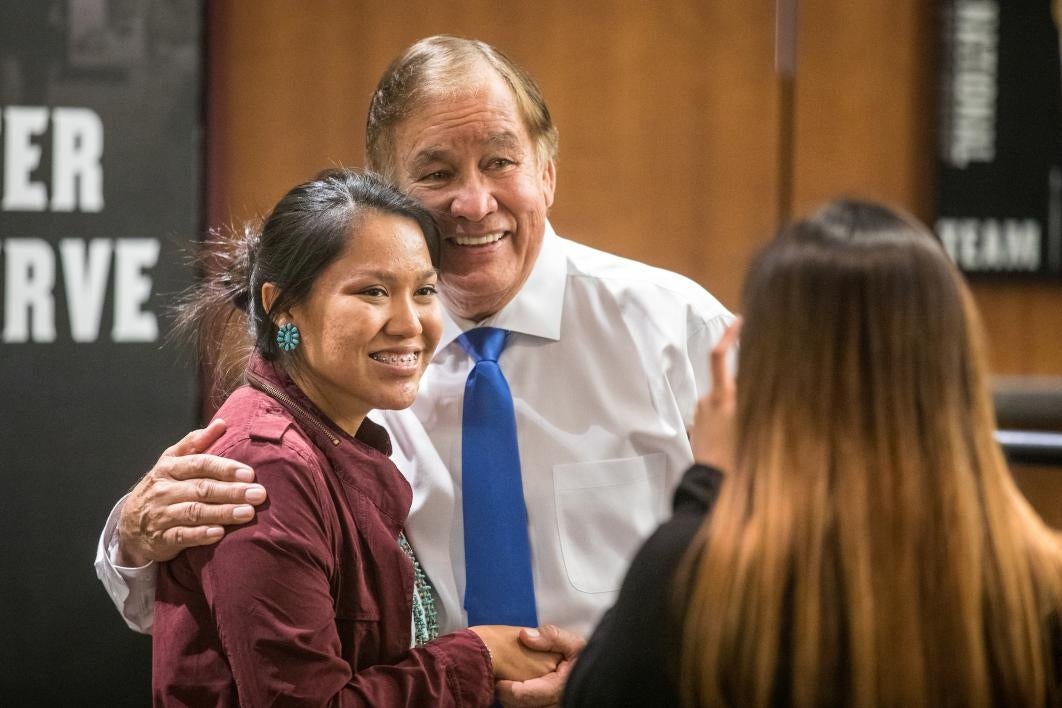

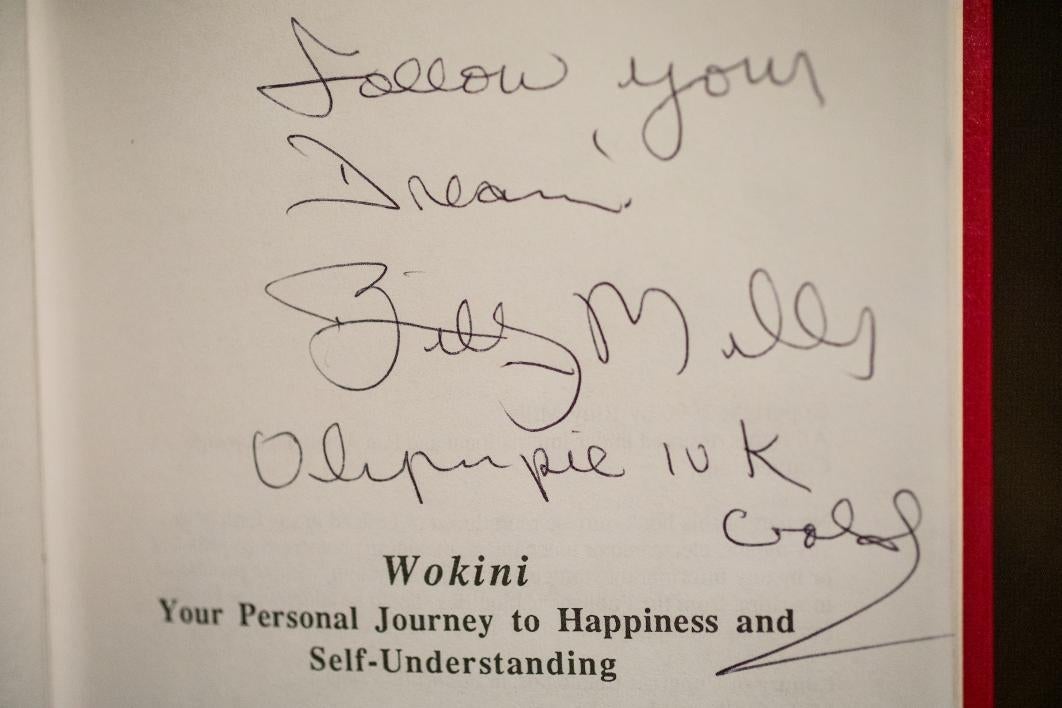

Top photo: Retired ASU environmental graphic designer Randy Kemp (left) shares a laugh with Billy Mills, the Sioux Olympic gold medalist who won the 1964 Tokyo 10,000 meters. Kemp took part in a 500-mile ultramarathon in 1979, sponsored in part by Mills, and had him sign his finisher's certificate. Mills later addressed around 100 people at the "Indigenous Identity and the Athletic Experience" event on the Tempe campus on Thursday. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now