Think about where you are right now. Your office chair, your living room couch, your spot of shady sidewalk. The land under your feet has a story to tell.

Postdoctoral Research Associate Emily Fioccoprile, an archaeologist with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change's Center for Archaeology and Society, has made it her mission to uncover that story. Only the land under her feet, so to speak, is the Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve.

From a distance, the preserve may seem unremarkable. It’s a patch of desert with a large hill of boulders at the center. Peer a little closer, however, and you’ll see that the orangey discolorations on the rocks have form. They’re pictures.

The preserve boasts the largest concentration of Native American rock art, called petroglyphs, in the Phoenix area. It’s a unique spot, because the petroglyphs there date from many different periods of time, meaning that different groups of people contributed to the hillside’s artwork.

VISIT THE PRESERVE: Free admission Saturday with downloadable ticket

“Multiple people came back over and over again,” Fioccoprile said. “This was an important enough place that they bothered climbing quite high up a very steep hill. They went to a lot of effort to make these.”

Fioccoprile has been studying how people of the past and of today have used the preserve to understand who they are. To do this, she looks at the archaeology of the site’s landscape much like a biographer would examine events over the course of a person’s life.

“Landscape biography is a nice model that gives you a connection across deep time. You can pick little snapshots, almost like chapters, of a place’s history, and then you can ask questions about those without losing sight of the big picture,” she said.

Now, she’s starting the next chapter of the preserve’s biography by helping the public interpret the landscape in new ways.

Lights … camera …

There are some petroglyphs that visitors just aren’t able to see, whether because the marks are too faded, too far away from the trail or too well hidden in the nooks and crannies of the hillside.

“I wondered, can we use nondestructive technologies to learn anything new about the petroglyphs that the public can’t see? And how would that impact the way people experience the landscape?” Fioccoprile said.

She decided to put this to the test with a high-definition camera and a technique known as reflectance transformation imaging.

The basic idea behind RTI is to take multiple photos of an object with the light at different angles. The changing shadows and highlights give researchers a better view of the object’s curves, cracks and edges.

At the preserve, Fioccoprile and her team of ASU researchers, students and volunteers chose petroglyphs that were on boulders with enough open area around them to safely set up a camera tripod. Then, one team member held a powerful flash bulb at the end of a long pole and moved it around in a dome-like pattern above the petroglyphs. Another team member remotely triggered the camera and flash for each photo.

After carefully saving the original, untouched, high-resolution pictures, Fioccoprile used software to combine them into detailed models that allowed her to virtually move light around the petroglyphs. For some harder-to-see petroglyphs, she used another program to adjust the colors and create a stronger contrast between the petroglyph and the rock panel.

Fioccoprile is careful to only clarify, not alter, what is physically present on the rocks. She also documents the changes, if any, that she makes to the photos so that future researchers can trace the steps she took from the original images.

“There’s a big responsibility to make sure that these images actually represent what you see in real life,” Fioccoprile said. “We try to interfere with these photos as minimally as possible.”

Her team also brought in a drone pilot, Douglas Gann, to take high-resolution photos of the petroglyphs from above. The pictures not only provide a detailed view of how the markings are spaced out on the landscape, but they also allowed the team to create a 3D model of the entire site.

That model, along with the other RTI models, photos and maps created during her research, will benefit the community in several ways. They’ll be archived for future researchers and heritage management professionals, serve as a resource for visitors to explore the petroglyphs they can’t make out from the trail and become the basis of a forthcoming exhibit at the Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve’s visitor center.

“I’m really passionate about making sure that what I do is something that someone off the street could understand and get excited about,” she said.

Filling in the blanks

The RTI and color processing techniques, it turns out, were enough to uncover an ancient mystery or two.

One came about unexpectedly when Fioccoprile did RTI on the preserve’s most famous boulder, which depicts two four-legged, deer-like animals touching noses, known as the “kissing deer” petroglyph.

“Sometimes, when I’m doing RTI on one of these animals, I do feel like I’m taking its portrait,” she said.

Though the petroglyphs on this panel are highly contrasted against the rock, their creator carved them very shallowly onto the surface. In fact, high-resolution photos reveal that the lines are so shallow they have little gaps in them — perhaps giving a clue about the maker’s priorities.

“It doesn’t seem to have been important to get a perfect line,” Fioccoprile said. “It was about the visual impact, rather than creating a continuous mark.”

She believes this rock panel is popular partly because visitors can easily recognize the animals it depicts, and in doing so, share an experience with people of the past. The deer, in a way, are celebrities and will be for generations to come.

Other petroglyphs, however, may have been completely forgotten by time were it not for Fioccoprile’s methods and the incredible knowledge of the preserve’s volunteers. One rock panel had a petroglyph of a one-pole ladder — a long vertical line with short horizontal lines crossing it — and another petroglyph of a footprint. But volunteer Peter Huegel advised using RTI to find a third petroglyph that he insisted was there.

Sure enough, as Fioccoprile later looked at a model of the panel on her computer, a second footprint slowly emerged from the rock. It was so faded, the site’s original surveyors of the ’70s and ’80s missed it entirely.

“There was a blank space on this panel which we now know is actually pretty full. And if you think about all the other blank spaces across the preserve, I wonder how many of them have petroglyphs which we don’t realize are there,” she said.

“It’s thrilling that we can still make discoveries almost 40 years after people first studied the site in depth,” she added. “We don’t know everything. I think that’s really exciting.”

Top photo: (From left) Deer Valley Petroglyph Preserve volunteers Joseph Sallak and Peter Huegel, School of Human Evolution and Social Change Postdoctoral Research Associate Emily Fioccoprile and Kendall Baller, doctoral student, do reflectance transformation imaging on a boulder at the preserve. Photo courtesy of Chris Reed

More Arts, humanities and education

AI literacy course prepares ASU students to set cultural norms for new technology

As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at Arizona State University, it’s essential for students to understand how to ethically wield this powerful technology.Lance…

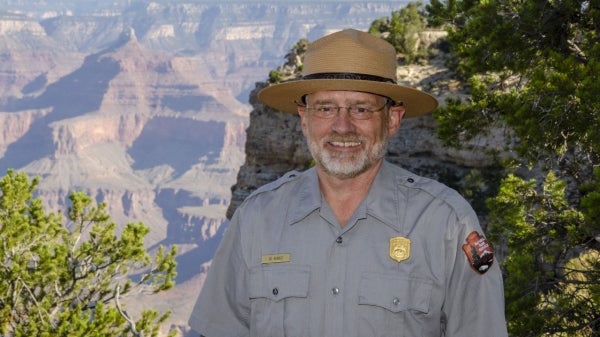

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the park was created, many were forced from those lands, sometimes at…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk is a subgenre of science fiction that explores the intersection of…