A lot can happen at 160 degrees Fahrenheit: Eggs fry, salmonella bacteria dies, and human skin will suffer third-degree burns. If a car is parked in the sun on a hot summer day, its dashboard can hit about 160 degrees in about an hour. One hour is also about how long it can take for a young child trapped in a car to suffer heat injury or even die from hyperthermia.

Researchers from Arizona State University and the University of California at San Diego School of Medicine have completed a study to compare how different types of cars warm up on hot days when exposed to different amounts of shade and sunlight for different periods of time. The research team also took into account how these differences would affect the body temperature of a hypothetical 2-year-old child left in a vehicle on a hot day. Their study was published today in the journal Temperature.

“Our study not only quantifies temperature differences inside vehicles parked in the shade and the sun, but it also makes clear that even parking a vehicle in the shade can be lethal to a small child,” said Nancy Selover, a climatologist and research professor in ASU’s School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning.

From January through May 2018, six children died after being left in hot cars in the United States. That number will go up. Annually in the U.S., an average of 37 children left in hot cars die from complications of hyperthermia — when the body warms to above 104 degrees and cannot cool down. More than 50 percent of cases of a child dying in a hot car involve a parent or caregiver who forgot the child in the car.

The findings

Researchers used six vehicles for the study: Two identical silver midsize sedans, two identical silver economy cars and two identical silver minivans. During three hot summer days with temperatures in the 100s in Tempe, Arizona, researchers moved the cars from sunlight to shade for different periods of time throughout the day. Researchers measured interior air temperature and surface temperatures throughout different parts of the day.

“These tests replicated what might happen during a shopping trip,” Selover said. “We wanted to know what the interior of each vehicle would be like after one hour, about the amount of time it would take to get groceries. I knew the temperatures would be hot, but I was surprised by the surface temperatures.”

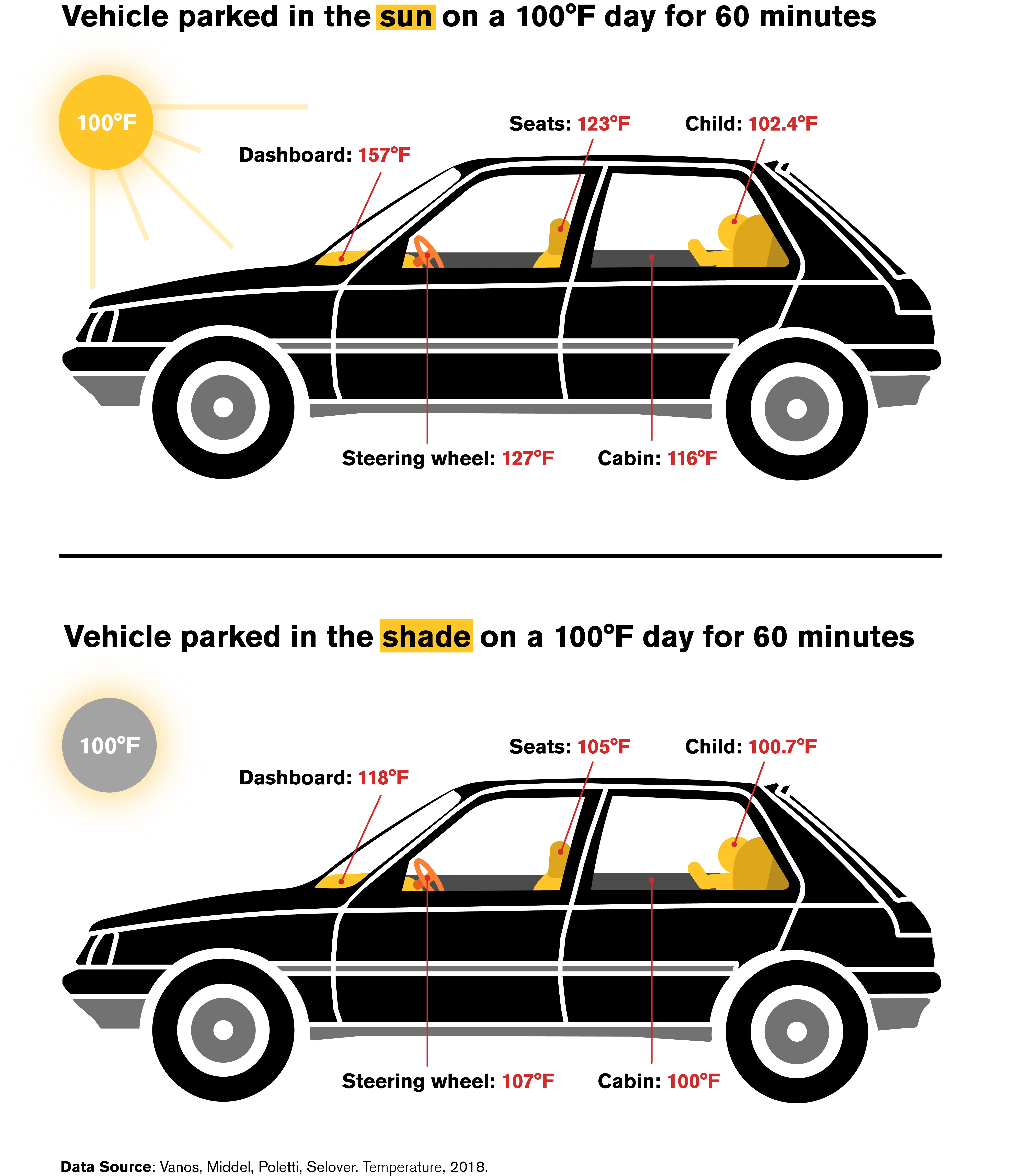

For vehicles parked in the sun during the simulated shopping trip, the average cabin temperature hit 116 degrees in one hour. Dashboards averaged 157 degrees, steering wheels 127 degrees, and seats 123 degrees in one hour.

For vehicles parked in the shade, interior temperatures were closer to 100 degrees after one hour. Dashboards averaged 118 degrees, steering wheels 107 degrees and seats 105 degrees after one hour.

The different types of vehicles tested warmed up at different rates, with the economy car warming faster than the midsize sedan and minivan.

“We’ve all gone back to our cars on hot days and have been barely able to touch the steering wheel,” Selover said. “But imagine what that would be like to a child trapped in a car seat. And once you introduce a person into these hot cars, they are exhaling humidity into the air. When there is more humidity in the air, a person can’t cool down by sweating because sweat won’t evaporate as quickly.”

Graphic by Safwat Saleem/ASU

Hyperthermia

A person’s age, weight, existing health problems and other factors, including clothing, will affect how and when heat becomes deadly. Scientists can’t predict exactly when a child will suffer a heatstroke, but most cases involve a child’s core body temperature rising above 104 degrees for an extended period.

In the study, the researchers used data to model a hypothetical 2-year-old boy’s body temperature. The team found that a child trapped in a car in the study’s conditions could reach that temperature in about an hour if a car is parked in the sun, and just under two hours if the car is parked in the shade.

“We hope these findings can be leveraged for the awareness and prevention of pediatric vehicular heatstroke and the creation and adoption of in-vehicle technology to alert parents of forgotten children,” said Jennifer Vanos, lead study author and assistant professor of climate and human health at UC San Diego.

Hyperthermia and heatstroke effects happen along a continuum, Vanos said. Internal injuries can begin at temperatures below 104 degrees, and some heatstroke survivors live with brain and organ damage.

Why memories fail

Forgetting a child in the car can happen to anyone, said Gene Brewer, an ASU associate professor of psychology. Brewer, who was not involved in the heat study, researches memory processes and has testified as an expert witness in a court case involving a parent whose child died in a hot car.

“Often these stories involve a distracted parent,” he said. “Memory failures are remarkably powerful, and they happen to everyone. There is no difference between gender, class, personality, race or other traits. Functionally, there isn’t much of a difference between forgetting your keys and forgetting your child in the car.”

Most people spend a lot of time on routine behaviors, doing the same activities over and over without thinking about them. For example, driving the same route to work, taking the children to day care on Tuesdays and Thursdays, or leaving car keys in the same spot every day. When new information comes into those routines, such as a parent’s day care drop-off day suddenly changing or an emergency phone call from a boss on the way to work, that’s when memory failures can occur.

“These cognitive failures have nothing to do with the child,” Brewer said. “The cognitive failure happens because someone’s mind has gone to a new place, and their routine has been disrupted. They are suddenly thinking about new things, and that leads to forgetfulness. Nobody in this world has an infallible memory.”

Ariane Middel, an assistant professor in Temple University’s Department of Geography and Urban Studies, and Michelle N. Poletti, a civil engineering student at Florida International University, also worked on the study as part of the National Science Foundation Central Arizona-Phoenix Long-Term Ecological Research Program through ASU.

More Health and medicine

The science of sibling dynamics: Why we fight, how we relate and why it matters

We have Mother’s Day, Father’s Day and even Grandparents’ Day. But siblings? Usually they get a hand-me-down sweatshirt and, with any luck, a lifetime of inside jokes.But actually, there is a…

New study seeks to combat national kidney shortage, improve availability for organ transplants

Chronic kidney disease affects one in seven adults in the United States. For two in 1,000 Americans, this disease will advance to kidney failure.End-stage renal failure has two primary…

New initiative aims to make nursing degrees more accessible

Isabella Koklys is graduating in December, so she won’t be one of the students using the Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation's mobile simulation unit that was launched Wednesday at Arizona…