Times sure have changed.

Young adult novelsYoung adult novels are intended for age 10 and up. used to be about dealing with rites of passage like parents getting divorced, or dating and menstruation.

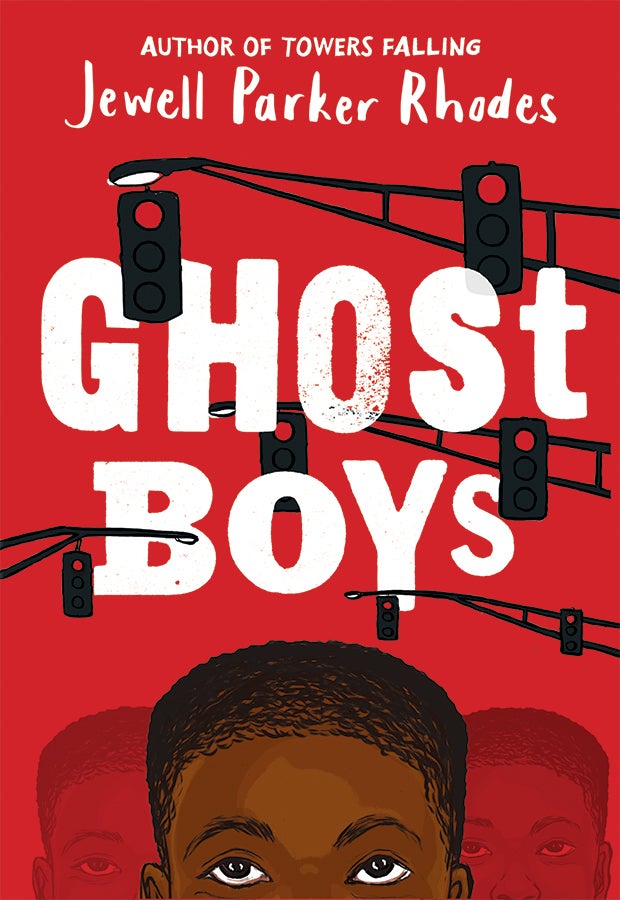

In Jewell Parker Rhodes’ new book, she writes about a 12-year-old boy getting gunned down by police who mistake his toy gun for a real threat.

“It’s not that I necessarily wanted to write this book, but it’s a necessary book for our times,” said Rhodes of her most personal book to date, “Ghost Boys,” which addresses police brutality and race relations. “Adults haven’t gotten this right, and it’s time to empower our kids so they can be the change to make this world a more just and livable place for people of color.”

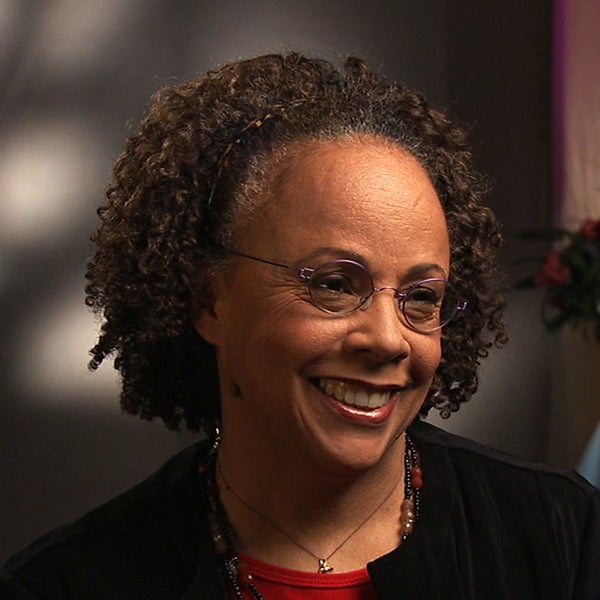

RhodesRhodes is also a professor of narrative study in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts. is the founding artistic director of Arizona State University's Virginia G. Piper Center for Creative Writing and a writing professor in the Department of English in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “Ghost Boys,” which will be released April 17, deftly weaves historical and sociopolitical layers into a gripping and poignant story about how children and families face the complexities of today’s world.

The acclaimed author and educator said she wrote "Ghost Boys" for several reasons, chiefly because she likes tackling hard subjects: "It allows me to grow as a writer. Otherwise, I won’t be a brave, courageous or valiant artist.”

Jewell Parker Rhodes

Question: You made an interesting literary choice in writing the narrative from a dead boy’s perspective. Why?

Answer: It was primarily because it was a theme in African-American culture that dead spirits are still with us and that they can still speak. My grandmother taught me at a very early age that spiritual essence always remains. It fit in with my theme that people's lives matter and the living have to make change so that it never happens again. It’s also to pay tribute to the dead. Oftentimes in books when people are dead, they don’t get to speak. Being able to allow Jerome, my main character, to speak, he is also able to speak for all the others that have been shot tragically.

I heard Jerome’s voice when writing this because he was real to me from the very beginning. He led me on a personal journey of all of my grief and rage with racism, prejudices and fears for my son and children of color being murdered by adults.

Q: How did you go about picking this subject matter?

A: When I finished my previous book, “Towers Falling,” I asked my editor what I should do next. She said, “What about the murder of young black boys?” I immediately said, “Nope, I’m not going to write that book.”

I’ve been writing for a long time and believe that words have power and words have the power to change the world. I also like to tackle hard subjects because when I do that, it makes me grow as a writer. I eventually came around to the idea that, isn’t this what I’ve been working towards my whole life? It was taking on the next emotional mountain because if I didn’t do it, I wouldn’t be brave, I wouldn’t be valiant. I wouldn’t be a courageous artist.

Middle schoolers deserve these stories because many of them, they are dying. So if you’re old enough to be shot at and killed, [you] are old enough to address this as a topic with a teacher or parent.

Q: Why did you initially say no to your editor?

A: I said no because it’s almost an impossible task. It was going to be hard to write it in a way that didn’t stereotype anyone and explored the complexity of racism and racial bias. Also in terms of creating something that was melodramatic, but not didactic to make it a living, breathing work that people could empathize with all of the characters and feel and understand the complexity.

There’s also an emotional cost because I’d have to purge all of my negative feelings in order to make it a cathartic experience. I remember so much hurtful stuff over the course of a lifetime. Racial divisions seem to be growing wider again, and [there is] too much civil unrest in our society. It took me two-and-a-half years to write what is essentially a very slim book. One of the reasons is that I would write a little bit, then I’d have such sadness. Then I’d have to take a break, but each time I took a break, I was renewed. I’d either add another character or add another layer or something that made the story richer. Eventually it all came together.

Q: You have tied the death of Emmett Till to the recent spate of police shootings in your book. Till was from another era but died in a similar fashion. Why did you introduce him as a character in the book?

A: Emmett Till died a year after I was born, and so his death played greatly on my mind in my youth. He was an innocent 14-year-old child who put his money down for bubblegum at a grocery store in Mississippi. That incident was not kept from me and so I knew about kids being killed through racism. We’ve had over time perhaps less overt racism, but it still exists. There is an unconscious bias of men of color that dates back hundreds of years. Those depictions have made a difference over the years, and it’s a very big pop-cultural manifestation — television images, story images and all sorts of negative associations we make with the color black or brown. Muslims are now suffering from those same negative associations. So that framing of "Yes, things have gotten better" doesn’t mean that it’s all gotten better.

The death that really impacted me was Tamir Rice in Cleveland. If you watch the video, it’s very clear the police car did not come to a full stop, and the officer jumped out and fired. There was no opportunity to Taser or stop him by other means and so he was shot. Then for four minutes, he lay there bleeding out. None of the police officers rendered aid until an EMT arrived on the scene.

To me, the camera and the body cam in a lot of these shootings show unjust acts. As a writer, I’m simply trying to make sense of it — that it’s not so clear-cut. If you’re an officer and you have an unconscious bias, then we need to weed that out. We need to be committed to change.

Q: The recent shooting of Stephon Clark in Sacramento, California, sadly makes “Ghost Boys” that much more relevant to readers.

A: Exactly. That happened when I was writing the book and became another news item of the day. I want this problem to stop and go away. Teens have enormous power and have the power to change, and they’ll be ready to vote in the blink of an eye. They’ll be able to make the change to help the world. Only the living can make things better.

Top illustration from the cover of "Ghost Boys."

More Arts, humanities and education

March Mammal Madness hypes science, storytelling in the classroom and beyond

In classrooms throughout the country, the buzz around March Mammal Madness starts long before the tournament begins. For middle school science teacher Jessica Harris, students wonder which…

Different ways of thinking, different ways of thriving: How ASU is supporting students with autism

According to the CDC, over 5.4 million adults in the U.S. are living with autism spectrum disorder, a condition that affects how individuals interact with others, learn and process information.…

Forever sewn in history

The historical significance of Black influence on fashion spans centuries. From the prints and styles of Africa to various American political climates, Black fashion has sealed its impact on the…