Take a sneak peek inside ASU's new Biodesign C building

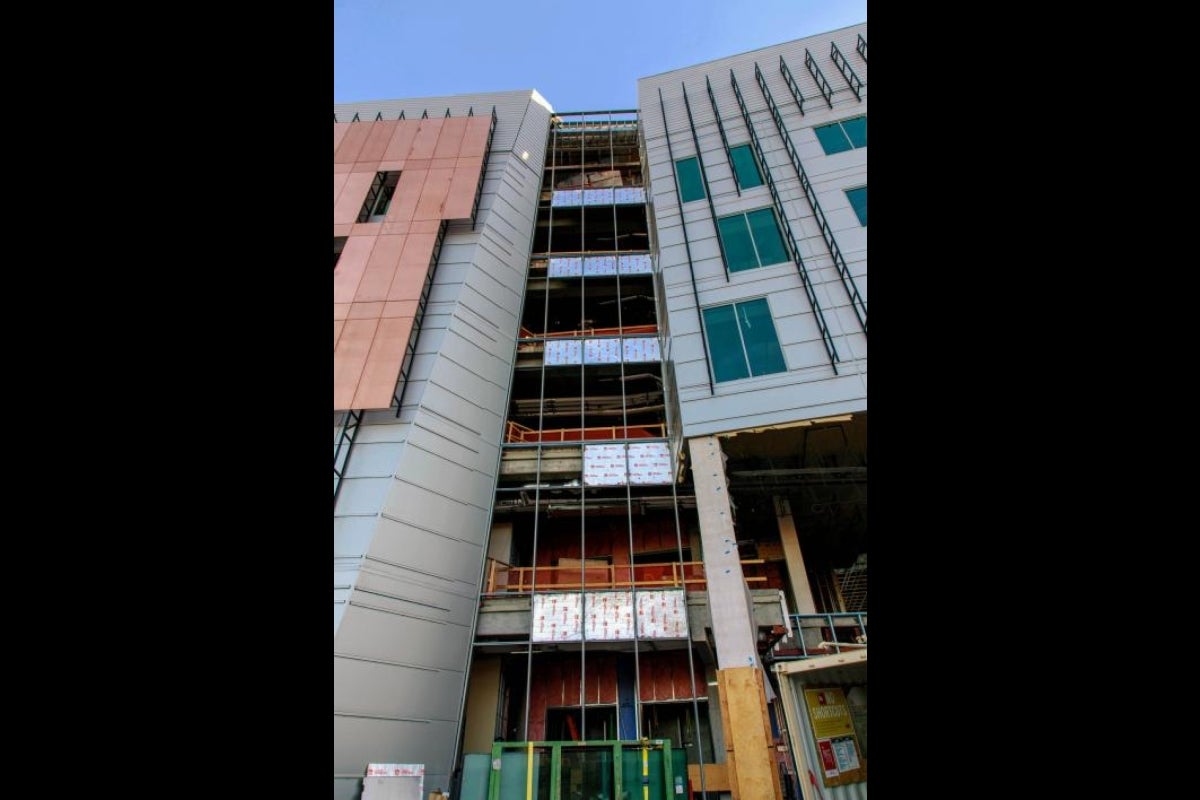

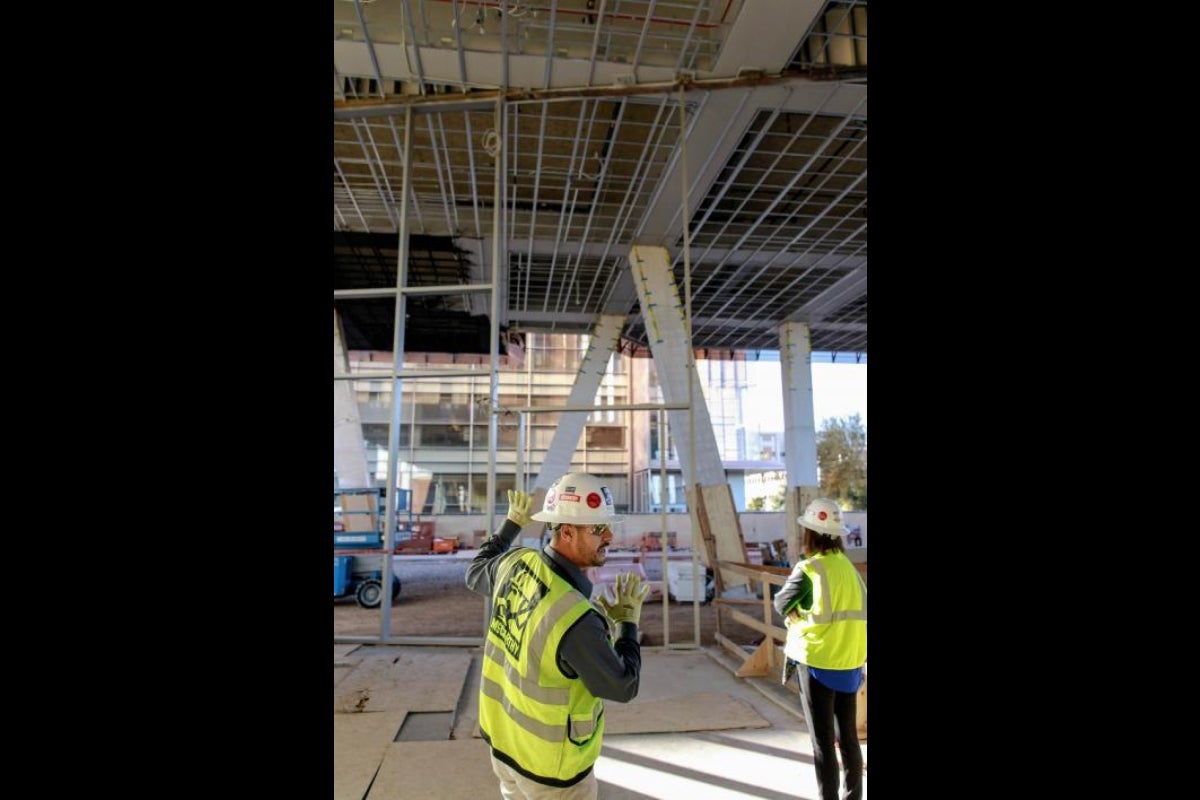

Though dust and construction equipment still fill the new Biodesign C building, it will be ready for research in just a few months. Photo by Ben Petersen

Biodesign C, the $120 million building expansion of the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, continues to rise along Rural Road at ASU’s Tempe campus.

Much of the building is now in place ahead of an April 2018 completion date. Biodesign staff recently toured the construction site for a sneak peek at the progress, and the project architects explained the building’s layout, infrastructure and appearance at a seminar in November.

It is the third building at ASU’s 14-acre master-planned Biodesign complex. The 189,000-square-foot structure includes 60,000 square feet of flexible laboratory space and office space, which will house nearly 400 researchers and staff, bringing the total size of Biodesign to 535,000 square feet and nearly 700 researchers. ASU's investment in the building and the lab equipment inside will total about $200 million.

Biodesign C is five stories tall, plus a basement. Its crown jewel lies in an underground vault: the world’s first compact X-ray free-electron laser. This innovative device will let scientists peer deep into molecular structure at a fraction of the cost of a typical free-electron laser. The new laser holds promise for drug discovery and bioenergy research.

The expansion is expected to draw top international scientific talent and grow ASU’s annual research expenditures by an estimated $60 million, supporting ASU’s goal of increasing research revenue to $850 million by 2025 and contributing an estimated $750 million to the Phoenix metro area in the coming decade.

Design thinking

“First and foremost, ASU wanted a workhorse research building that maximizes its investment,” said Erik Halle, ASU’s director of research facilities and infrastructure. It had to be 100-percent reliable, highly efficient and easy to operate and maintain. The successful design proposal took it a step further, thinking deeply about how the design could stimulate the Biodesign Institute’s unique, nature-inspired approach to research.

More than 20 design firms submitted proposals, and the university selected ZGF Architects and BWS Architects for the project. “These are two very highly skilled architects for what we believe to be an extraordinary and successful project for ASU,” Halle said.

Inspired by ASU’s institutional design aspirations and the Biodesign mission, the architects designed the building around a concept of research neighborhoods. “The form of the building grew from the idea of how we wanted it to function. It’s an embodiment of the type of collaboration we expect to see in the Institute,” said Gary Cabo, principal at ZGF Architects.

Biodesign scientists specialize in an entrepreneurial mindset to translate their discoveries into societal impact. The building’s open neighborhood model encourages collaboration between scientists of different disciplines. It also accommodates different forms of research with specific infrastructure and equipment needs, including chemistry, biological sciences and engineering.

Biodesign C will house a number of new and expanded programs, including the new ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center. Led by Eric Reiman, it is expected to be one of the world’s largest basic science centers for the study of Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. The C building will also house an expanded Biodesign Center for Mechanisms of Evolution led by Michael Lynch.

Sense of place

Located at a major eastern entry point for ASU’s Tempe campus and visible from miles away, Biodesign C is a striking addition to the neighborhood. It sits steps away from a major transportation hub connected by Valley Metro light rail, ASU’s intercampus shuttle and city buses, along Tempe’s busy Rural Road and between two parking garages.

The C building’s distinctive, wraparound copper skin emphasizes Biodesign’s Arizona roots (copper being one of Arizona’s historic “Five C’s” that drove the state’s early economy) and shields the building from sun exposure. Beneath this outer skin lies another metal skin that Cabo compared to a refrigerator door to further insulate the building. The space between the two skins acts like a chimney, allowing hot air to escape.

“This is the highest-performing building from an energy and technology standpoint on a campus that is known for excellent stewardship of the environment,” Cabo said. Biodesign C is targeting the rigorous LEED Platinum certification, building on a Biodesign tradition — Biodesign B was the first LEED Platinum building in Arizona.

“As an institution, Arizona State University is at the forefront of innovation in energy and performance in buildings,” said Robin Shambach, managing principal at BWS Architects. “Our goal was to be 50 percent better than similar research facilities, and Biodesign C will exceed that goal.”

Despite the extensive shielding to withstand Arizona summers, natural light fills the interior. The building boasts impressive views of Tempe in all directions and the neighborhood layout offers clear lines of sight through lab and office spaces. Biodesign C is adjacent to one of the largest areas of green space on the urban Tempe campus, which includes a desert garden and the James Turrell “Skyspace: Air Apparent” public art installation.

Biodesign C connects to the existing Biodesign B building underground; above ground, they connect visually via a shaded patio and glass lobby outside the Biodesign cafe. The design also leaves room for a possible fourth research building in the future.

Innovative construction

Advanced building techniques made the Biodesign C building possible.

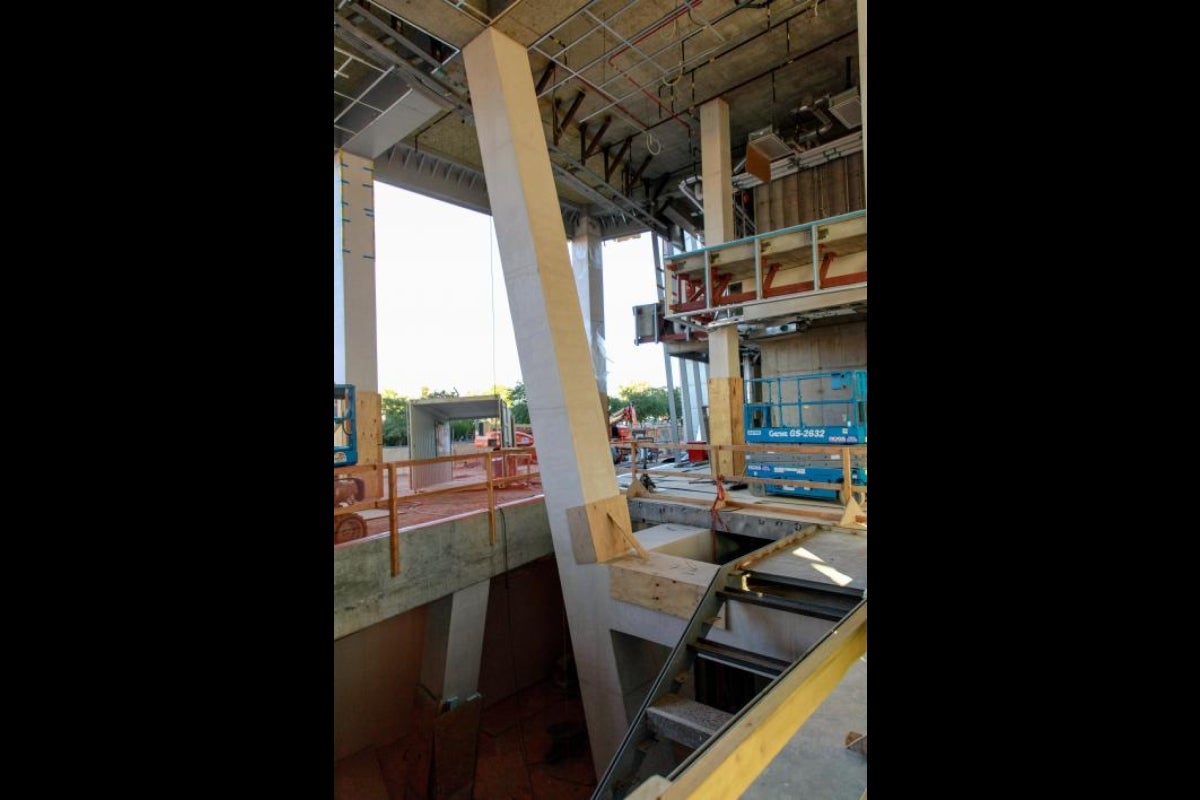

“Successful architecture is not unlike research,” Halle said. “It can be incredibly complex. It is dealing with the minutiae of everything, and at the same time it embodies bold visions.” The basement, housing the world’s first compact X-ray free-electron laser (CXFEL), exemplifies this idea.

Free-electron lasers help scientists to better understand the cellular mechanics of diseases such as cancer and processes including photosynthesis, accelerating research for new treatments and energy sources. Biodesign scientists William Graves and Mark Holl have collaborated with the architects, structural engineers and general contractor McCarthy Construction to shield the custom-built laser from outside interference.

This meant a lot of problem-solving: minimizing vibration from passing light rail trains, reducing magnetic fields in building materials and containing the energy from the laser beam. The lead-lined laser vaults feature an isolated four to six foot concrete mat slab that required a special overnight pour from more than 100 cement trucks, four foot thick concrete walls, a Faraday cage structure, demagnetized steel rebar, electronic safety features and a state-of-the-art control room.

ASU’s compact laser has the potential to relieve a scientific traffic jam and dramatically shrink the cost of this technology. Currently, there are only four XFEL facilities worldwide, including the $700 million, two-mile-long Stanford Linear Accelerator Center. Capacity simply cannot keep up with demand from researchers, and 80 percent of requests to use the technology are denied.

ASU’s CXFEL will also be about 100 times smaller and cheaper than a typical XFEL. ASU expects the Biodesign C laser will attract scientists from around the world and further grow the university’s reputation as a leading hub for research, innovation and discovery.

McCarthy Construction built and tested mock-ups of building components before they went up, including concrete slabs, columns and exterior panels. Biodesign C also features an innovative high-performance HVAC system that conserves energy while keeping labs properly ventilated and temperature controlled. Construction will be completed in April 2018.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…