How can apps get users to generate content? ASU study finds gender differences

China’s largest recipe-sharing platform needed a carrot to motivate more content from users, and research from a team of Arizona State University professors was able to pinpoint what works.

A new study by faculty in the W. P. Carey School of Business found that specific kinds of notifications could elicit more content from the app users — and that there are differences between men and women. Feedback that promoted a message of helping others prompted women to contribute more content, while men were more likely to respond to competitive messages.

The findings are an example of use-inspired research — important because many huge companies are dependent on user-created content, and they are constantly looking for ways to prompt customers to contribute.

Ni Huang, an assistant professor of information systems at ASU and the lead author, said that the teamThe other authors are Bin Gu, a professor of information systems, and Chen Liang, a doctoral student, both from the W. P. Carey School of Business at ASU, and Gordon Burtch, an assistant professor in the the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota. Gu is the Earl and Gladys Davis Distinguished Professor and is associate dean for China programs at the W. P. Carey School of Business. worked with Meishi, a Chinese company that owns the largest recipe-sharing smartphone application in China, in which users contribute and rate one another’s recipes.

Also on the research team was Yili Hong, an assistant professor of information systems at ASU who has done previous research on companies that require user-generated content.

“One of the questions that resonated with me was that they have tens of millions users but guess how many contribute? Less than 10 percent,” he said of the recipe app.

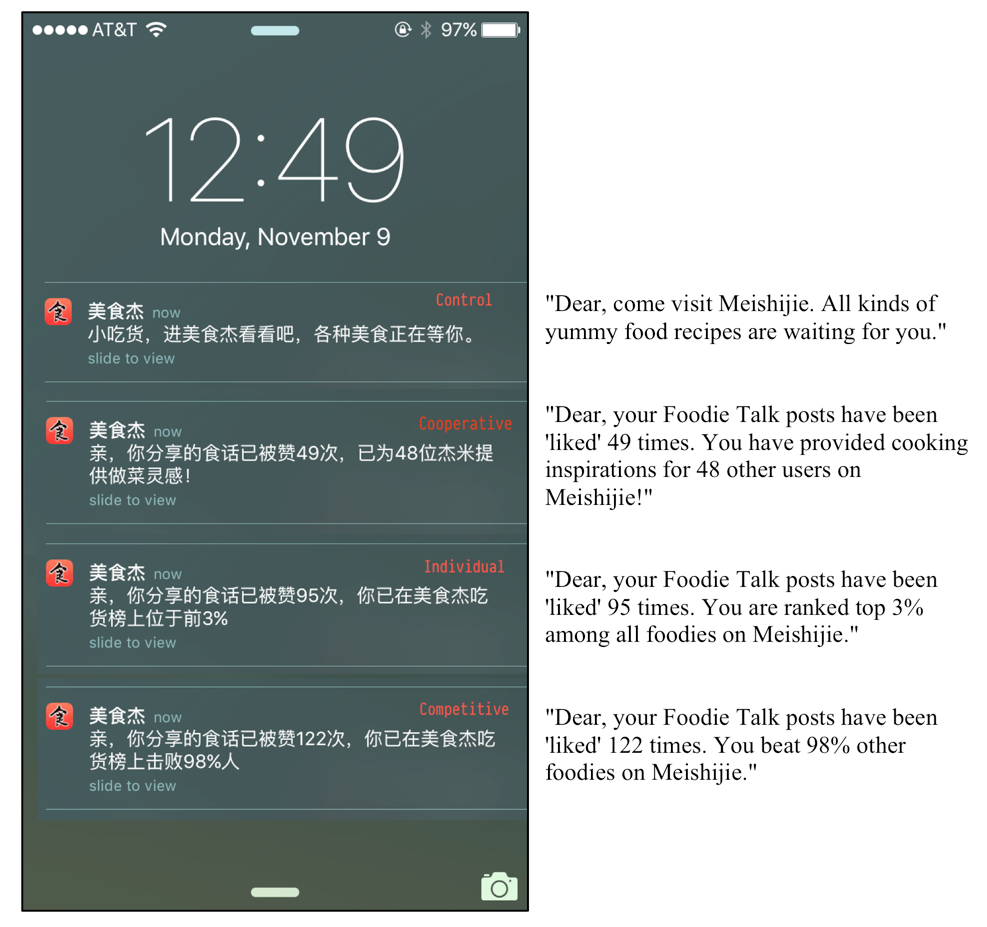

The Chinese company agreed to let the researchers perform the study with all the users in the new “foodie talk” section of the platform, and the 1,129 subjects were divided into four groups. Each group received a different kind of push alert on their smartphones once a week for seven weeks, and then their content contributions for the following week were recorded.

App users received different types of push notifications.

The control group received a generic message inviting users to look at the app, Huang said.

“Most of the time we find that kind of message is not very effective compared to when you provide performance feedback, how well you are doing in terms of the content you’ve contributed,” she said.

The other groups received feedback on how many “likes” they had, but the content was framed in different ways. One group’s push alerts gave the number of “likes” and emphasized how much they helped other people, saying, “You have provided cooking inspiration” for X number of other users.

Another group received a push alert giving a ranking, such as “you are in the top 3 percent of users.” This is “individualist” framing.

The fourth group was competitive, comparing performance, such as “you beat 98 percent of other foodies.”

The results differed by gender. In the group that received the “helpful” messages, everyone produced more content, but the effect was bigger for women, who contributed about 6 percent more postings than the control group. The “helpful” feedback prompted males to contribute about 2 percent more postings than the control.

In the competitive group, males generated nearly 11 percent more content than the males in the control group — but females responded negatively, uploading about 2 percent fewer postings than females in the control group.

“For females, if you tell them they’re outperforming other people, they’ll actually contribute less,” Hong said.

There was little difference between males and females who received the “individualist” messages with a ranking, Huang said.

The study also compared engaged users, who were already contributing a lot of good content, with users who contributed but did not receive a lot of “likes.”

“Think of it like ‘good students’ and ‘poor students,’ ” Hong said. “When we give this performance feedback, the good students will be more responsive and do even better, but when we tell the poor students this feedback, they’re less responsive. It’s demotivating.”

Companies that rely on user content already know that feedback generates more content among users, and they try a variety of methods to incentivize them.

“But no one knows which practice works or how to optimize for different users and genders, and that is the main contribution of this paper,” Hong said.

When the team submitted the paper to the journal Management Science, the editors were concerned that because the experiment involved cooking, an activity that could be considered female-oriented, the results might not be generalizable. So the group did another crowd-sourcing experiment, using 1,000 online subjects in the United States to rate (non-cooking-related) content, and replicated the results. The paper was accepted and published Aug. 31. Find the study here.

The Chinese app company was excited about the results and asked the team to do more research.

“If you think about the results, we were only looking at people who are already contributing some sort of content, and getting some likes,” Hong said. “But if a person has never contributed anything, how can you convert them into someone who is engaged? Is there a way to nudge them?”

The researchers are looking at the concept of fairness: “We’re using that concept to say, ‘You have benefitted from others; why don’t you try something yourself?’ ” They hope to produce another paper on that topic.

More Science and technology

Ancient sea creatures offer fresh insights into cancer

Sponges are among the oldest animals on Earth, dating back at least 600 million years. Comprising thousands of species, some with lifespans of up to 10,000 years, they are a biological enigma.…

When is a tomato more than a tomato? Crow guides class to a wider view of technology

How is a tomato a type of technology?Arizona State University President Michael Crow stood in front of a classroom full of students, holding up a tomato.“This object does not exist in nature,” he…

Student exploring how AI can assist people with vision loss

Partial vision loss can make life challenging for more than 6 million Americans. People with visual disabilities that can’t be remedied with glasses or contacts can sometimes struggle to safely…