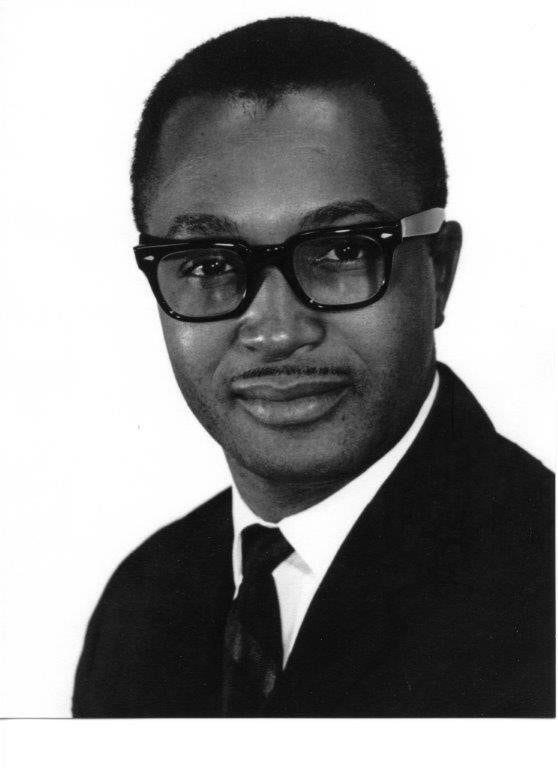

Remembering ASU's first black professor, who taught aspiring teachers in the 1960s

In the May 11,1966, edition of Arizona State University’s The State Press, a story near the back is headlined, “63 Faculty Members Are Promoted.” Similar stories appeared in the student-run newspaper every spring, each with a simple roster of faculty members advancing to the next level of their ASU careers. What made the May ’66 list of promotions more consequential was this: “Advance from instructor to assistant professor … John Edwards, elementary education.”

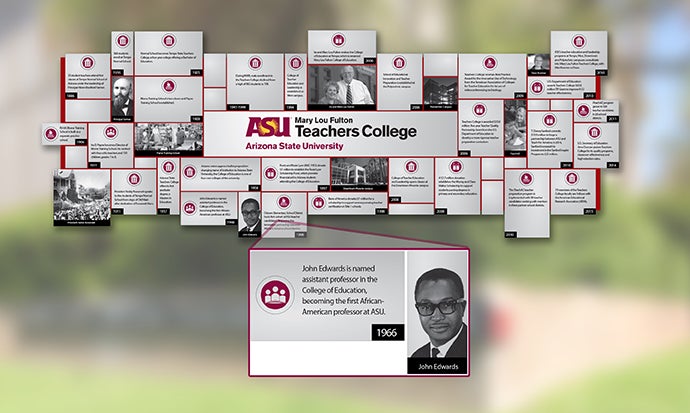

With this appointment in the School of Education, John Edwards became ASU’s first African-American professor. He is being honored with a panel on the timeline of Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College history in the Farmer Education Building on ASU’s Tempe campus.

His appointment came during a tumultuous time in America and on the ASU campus. The week that Edwards’ promotion appeared in The State Press, more than a million U.S. college students were preparing for the May 14 deferment examination that might protect them from President Lyndon Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. A few weeks before, the ASU chapters of Students for a Democratic Society and Young Americans for Freedom held competing rallies — “End of War” and “Win the War” — in front of Danforth Chapel.

The civil rights movement was roiling the campus as well. Leo Vichules, assistant professor of political science, accused the ASU Executive Council of refusing to consider an application for recognition as an on-campus student group from the Congress of Racial Equality. A discussion of integration on “Thursday at Nine,” the live panel discussion and call-in program on ASU-owned KAET-TV, brought a record response of 131 calls. And in a letter to the editor of The State Press titled, “Muhammed speaks,” a reader suggested “the Black Muslim representative” protesting at the corner of College and Orange should be escorted off the campus.

John Edwards was ASU's first black professor, teaching in the college of education in the 1960s.

Indianan in Arizona

Edwards was born in Muncie, Indiana, in 1930, one of nine children. He graduated from Muncie’s Ball State University and was drafted for the Army shortly thereafter. During his service, Edwards made friends from the Phoenix area, and, after his discharge, they recommended him for a teaching position in the Roosevelt School District in a historically African-American area of South Phoenix. He enrolled at ASU for one course in order to pass his teacher certification exam on the Arizona constitution.

“I taught at Percy L. Julian School, working with students from a disadvantaged area,” he would later recall. “They were the nicest kids. They wanted to learn, and it was my job to make sure they learned something in my classes. They would stay after school, and they would be be there long before the school opened. They were so excited.”

He also volunteered his time as scoutmaster for a Boy Scout troop. That, combined with “all those things you have to do in a public school — you put those together and there’s not enough hours in the day to do everything. But somehow I managed to do it.”

He also managed to meet and marry Mavis Jones (MAE ’64), a North Carolina native who had come to Arizona to teach. “Arizona was in a tremendous growth period,” he recalled. “They needed people and had problems recruiting teachers. Mavis said, ‘I won’t have to shovel snow! I can drive my car without chains! I think I’ll give it a try.’”

During his first few years of teaching, Edwards enrolled again at ASU, earning his master’s degree in social studies in 1959. After a professor suggested there might be an associate faculty position for him in the college of education, Edwards was hired to teach a course listed in the catalog as Problems of Teachers. He called it “Teaching Teachers to Teach.”

“Discipline was number one,” Edwards said. “Anybody who’s ever taught school will tell you that’s the number one problem. It’s how you handle young people that makes discipline easy or difficult. You can’t just yell at them. You have to talk to them, show them you respect them, that you love them, that you will see them through.” The care and commitment he showed his students at Julian would also become a hallmark of his higher education career.

Catching fire

Edwards became an instructor in the Department of Adult Education in 1964, teaching reading in Guadalupe, Arizona. He recalled President Johnson’s State of the Union address that year that launched the administration’s War on Poverty, and said, “That’s when I caught fire. Many adults in that area hadn’t learned to read or write. I don’t think there’s anything as great as when an adult would come to me, crying, and say, ‘I learned to read last night!’”

He completed his doctoral degree in elementary education the following year and was named an assistant professor of elementary education in 1966.

Edwards’ career as an ASU professor was remarkable not only for erasing a color line, but for its breadth and richness. Between 1966 and his retirement in 1996, he became associate professor, then full professor; served as assistant dean, and eventually as associate dean of university continuing education and associate director of summer sessions. He was a consultant for 31 Arizona school districts and those of five other states. He directed two projects for the U.S. Department of Education and served on the boards of eight others. Edwards co-authored two books, wrote several extensive articles and edited 13 manuals to accompany instructional television programs. He received more than a dozen awards in recognition of his efforts on behalf of literacy, civic engagement and equality.

Legacy of education

Edwards died in 2013. For all his academic and community accomplishments, he might have been most proud of the recollections shared by his family: Mavis, sons John Jr. (now deceased) and Robert, and daughter Janice Edwards-Jackson.

“He was fun and funny,” said Mavis Edwards. “He liked to dance and he loved good music. But he liked to get things done. He was always planning, and he always got them done.”

Janice said, “My dad was always willing to help others and provide guidance and support — especially to ASU students — regardless of their situation or needs.”

“He did not like uneven playing fields,” Robert Edwards said. “If he smelled an injustice, he went after it.”

Still, his children all noted that Edwards rarely spoke with them of injustices he personally had faced. He had been refused membership in the honor society at his own high school, then only recently integrated, until white faculty members advocated for him.

“I had a lot of support,” Edwards said. “But that was an eye-opener for me, and I think for them, too.”

John Edwards Jr. recalled seeing a newspaper clipping from the Muncie newspaper announcing his father’s promotion to Eagle Scout. The headline read, “Eagle Rank to Colored Boy.”

“Many of those kinds of things we found out later in life,” he said. “He just told us he was an Eagle Scout. He didn’t brag about himself.”

Janice Edwards-Jackson said her father was a champion of education as a solution to inequality. “Everything in our family centered on education,” she said. “My mom was a teacher, a librarian and a principal. We were never going to be allowed to use race as an excuse.”

And all of them remembered the family meals. Robert Edwards said, “Mom is a phenomenal cook. We would always eat as a family. That’s when we learned to think.”

“They didn’t tell us what to think, but how to think," said Edwards-Jackson.

The Edwards children weren’t the only members of the next generation to benefit from those mealtimes. John Edwards Sr., who believed all students need their teachers’ respect and love, was well known for bringing ASU students home to his family’s table.

“Yes,” Mavis Edwards recalled, “We fed quite a few.”

Top photo: The panel featuring John Edwards, the first black professor at ASU, was added to the timeline in the Farmer Education Building on the Tempe campus.

More Arts, humanities and education

‘It all started at ASU’: Football player, theater alum makes the big screen

For filmmaker Ben Fritz, everything is about connection, relationships and overcoming expectations. “It’s about seeing people beyond how they see themselves,” he said. “When you create a space…

Lost languages mean lost cultures

By Alyssa Arns and Kristen LaRue-SandlerWhat if your language disappeared?Over the span of human existence, civilizations have come and gone. For many, the absence of written records means we know…

ASU graduate education programs are again ranked among best

Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton College for Teaching and Learning Innovation continues to be one of the best graduate colleges of education in the United States, according to the…