Think your tech is cool? Wait until you see what Umit Ogras is working on.

“If we accomplish this, smartphones and tablets will have a new form,” said the electrical engineer at Arizona State University. “You don’t always carry your phone. You always wear a shirt.”

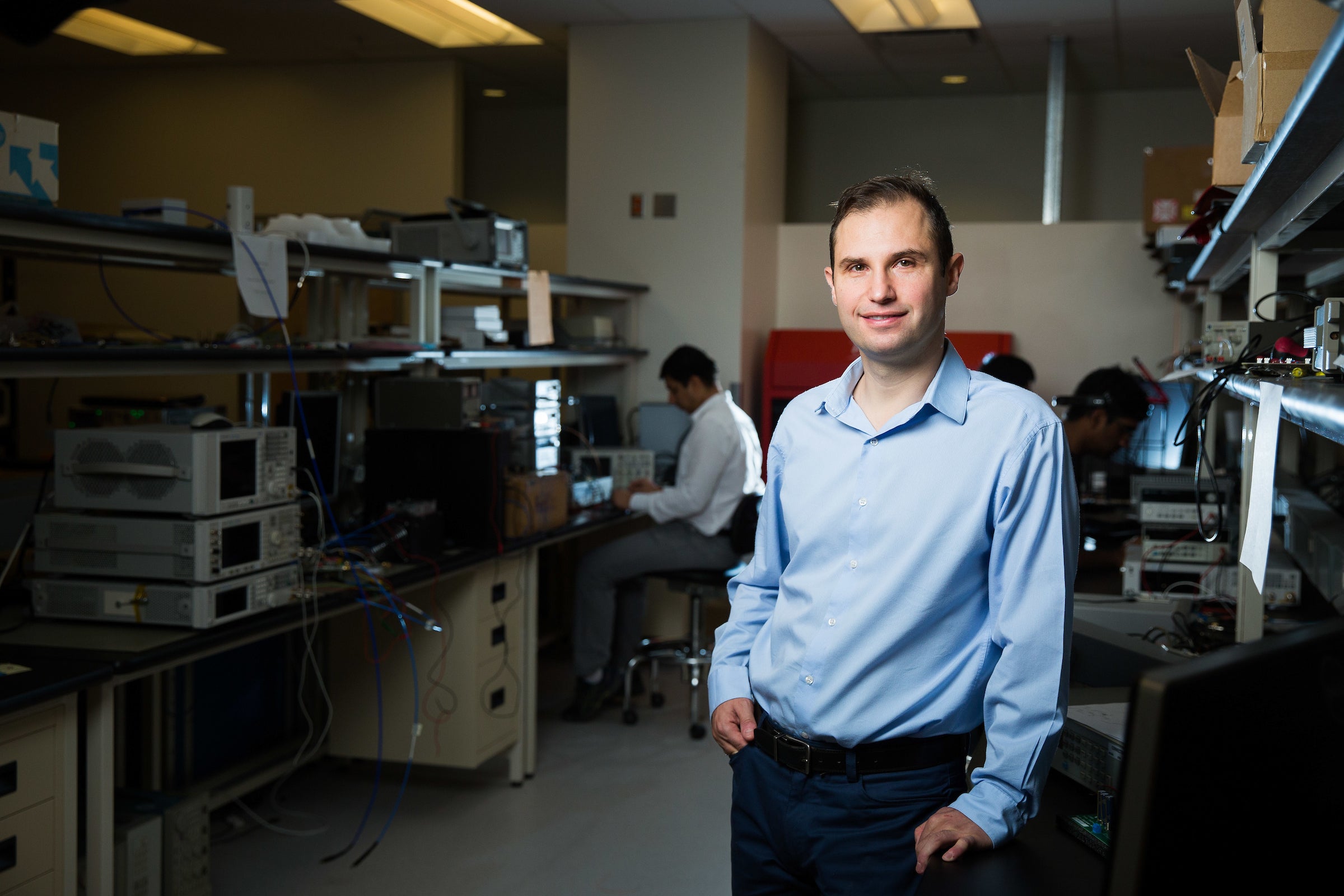

Umit Ogras

Flexible hybrid electronics can be bent or stretched. Picture pulling a wand from your pocket, unfurling a scroll, and watching a movie on a desktop-size screen.

Watching TV at home? Wave your arm and change channels. In the hospital? A disposable patch on your arm will use wireless connections to transmit data about blood pressure, heart rates and other vital signs to doctors and nurses. Wear a Fitbit watch when you go for a jog? That’s going to disappear into your sleeve, and it’s going to have scores more functions.

Ogras, an assistant professor in the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, recently won a five-year, $500,000 early-career development grant from the National Science Foundation to continue developing flexible hybrid electronics.

“It makes wearable devices beyond watches,” Ogras said. “We want to make them totally flexible.”

Computers have gone from room-size in the 1950s to desktops in the 1980s to handhelds today. Ogras’ research takes them into the next realm.

“The smartphone can disappear if we wear it in our clothes,” he said.

Health, motion and gesture monitoring will revolutionize personal devices. Ogras envisions mute people wearing a glove that will interpret sign language and literally “voice” communication. Wheelchairs will be controlled by arm motion instead of a joystick. Maps and GPS can be incorporated into devices.

“It knows your location in the house and where you want to go,” Ogras said.

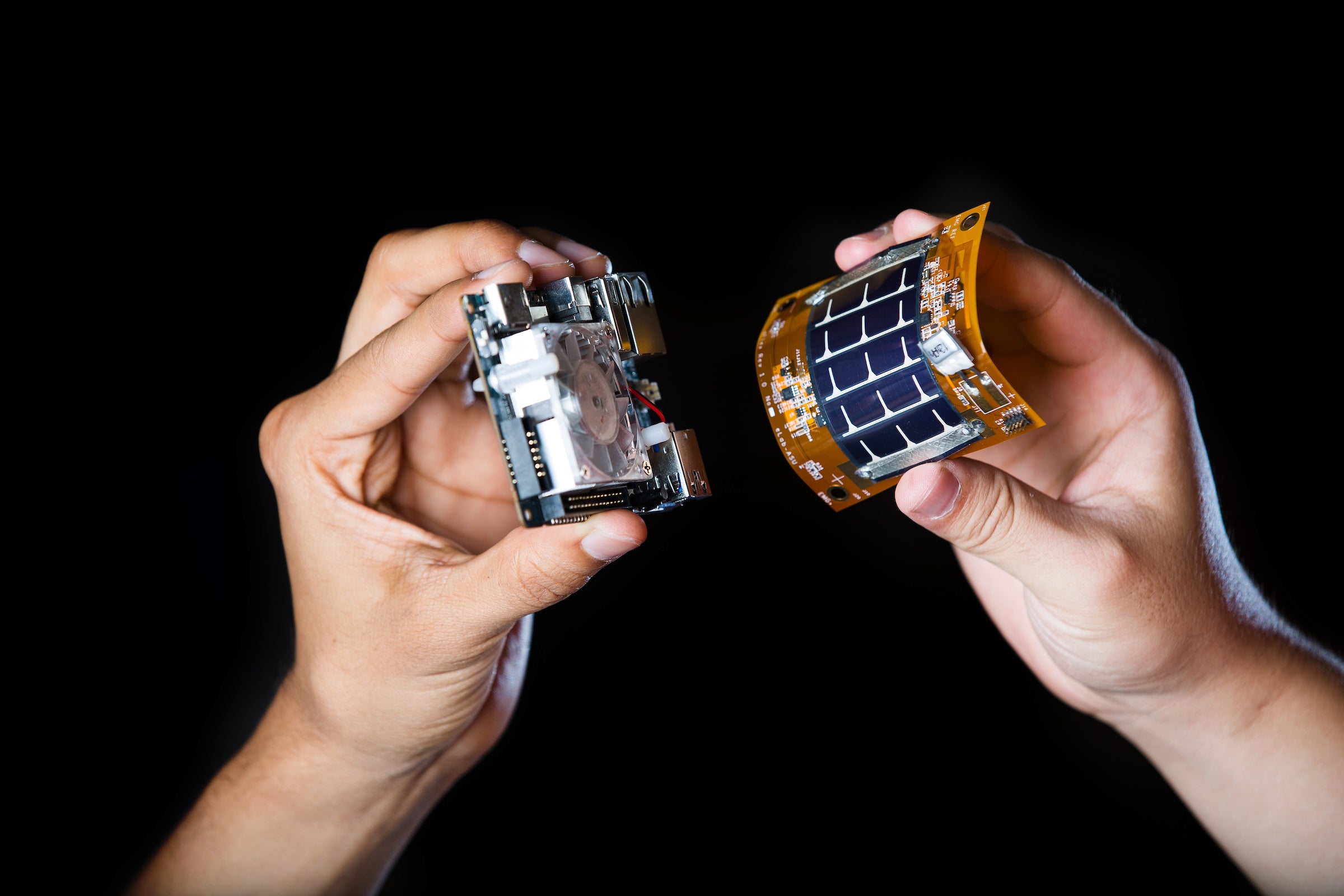

Graduate students show an example of a traditional electric board (left) and the flexible, solar-powered board that can be used in wearable monitors in ASU Assistant Professor Umit Ogras' lab in Tempe on June 28. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Three of the biggest problems Ogras is working to crack are the cost, size and battery.

His electronics use photovoltaic cells instead of batteries. The solar panels charge a small flexible battery during the day, which powers the electronics at night. The battery is 200 times less powerful than the battery in a typical smartphone. (It’s also 50 times lighter than a typical smartphone battery.) Energy harvesting is crucial.

Ogras has been working on the research for three years. He worked at Intel Corporation on smartphones — systems running on chips. His devices will run systems on polymer.

“We hope other people will start working in this domain,” he said.

The NSF Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) Program offers awards in support of early-career faculty who have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education and to lead advances in the mission of their department or organization.

Fourteen ASU faculty won the award this year. Typically the NSF funds about 350 CAREER faculty each year.

Top photo: ASU students show an example of a silicon-based element with embedded electrodes that will be able to sense movement in body parts in Assistant Professor Umit Ogras' lab. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…