Proteins help account for the complexity and astonishing diversity among humans (and other living forms). They are the body’s workhorses, forming muscles, bones, cartilage, skin and blood; facilitating essential chemical reactions and protecting us from disease.

The sequencing of the human genome, however, presented science with a puzzle: despite their enormous physical variability, humans only have around 20,000 genes capable of coding for these proteins. How can this tiny complement of genes — fewer than the number of genes found in the lowly tomato plant — account for the richness and variability found in humans?

According to Marco Mangone, a researcher at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute, part of this dilemma has to do with misperceptions of just what a gene is and what governs its behavior.

Researchers have a fair understanding of the starting sequence for genes, since historically most investigations focused on their mapping in the genome. The endings of genes, however are more problematic. The issue has been difficult to study and even today, a unanimous agreement among scientists about where genes terminate is lacking.

Mangone has studied this last portion of a gene, a domain known as the 3’Untranslated Region (or 3’UTR), because it does not contain information to make a protein. 3’UTRs have been largely ignored in past research, viewed as a kind of afterthought to the vital information in the body of the gene, where the sequence information to make a protein resides.

Marco Mangone is a researcher at the Biodesign Center for Personalized Diagnostics and assistant professor in ASU's School of Life Sciences

It turns out, however, that the 3’UTR plays a critical role in the regulation of gene expression, exerting control over the final step in protein manufacture, known as translation. Through the effect of the 3’ UTR, genes can be tightly regulated, selectively blocking some of them from successfully becoming protein. Even if a given gene has already made it to the halfway point and been transcribed into mRNA, the 3’UTR regions dictate when and how a given gene will complete its journey into protein, through translation.

Hence, knowledge of 3’ UTRs is central to a full picture of the complex ways in which our genes actually behave. Unfortunately, 3’UTRs and their related regulatory networks are poorly understood in most organisms.

It has been recognized for some time that certain 3’ UTRs are significantly misregulated in many diseases. Global shortening of 3’ UTRs has been linked with cancer development, for example, with such abbreviated transcripts occurring with high frequency in colorectal, breast and lung cancer samples. Shortened 3’ UTRs have also been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease, autism and muscular dystrophy.

Scientists like Mangone are focusing more intently on characterizing this last portion of the gene, since understanding the underlying rules governing 3’UTR control of gene expression may hold the key to finding more definitive cures for these diseases. He devises and applies methods to uniformly map the ends of genes, and to study the way in which they are regulated after they are transcribed from DNA into mRNA, but before they are translated into proteins.

In the current study, recently published in the journal Genetics, Mangone and his colleagues have sequenced 3’UTRs of expressed genes from eight large somatic tissues of the nematode worm C. elegans, and shown that:

- There is a striking variability in term of 3’UTRs length for a given gene in different somatic tissues in multicellular (or metazoan) life forms.

- Different 3’UTRs are both deliberate and functional, meaning different sequences of 3’UTRs (known as isoforms) are specific to certain tissues, and their presence serves a purpose in the regulation of gene expression.

- A shortened 3’UTR allows mRNA transcripts to evade regulation by regulatory molecules, such as microRNA — short, non-coding RNA fragments that often target mRNAs for silencing, thereby blocking their translation into protein.

In brief, longer 3’ UTRs allow more binding sites for regulatory molecules to attach and switch off translation into protein while shorter 3’ UTRs allow genes to evade regulation and complete their translation into protein. Through this mechanism, the body can finely tune gene expression on a tissue by tissue basis.

This new research marks the first time the dynamics of 3’UTR regions have been observed within a living organism. In a series of novel experiments, the authors show that 3’UTR isoforms occur within C. elegans in a tissue-specific manner.

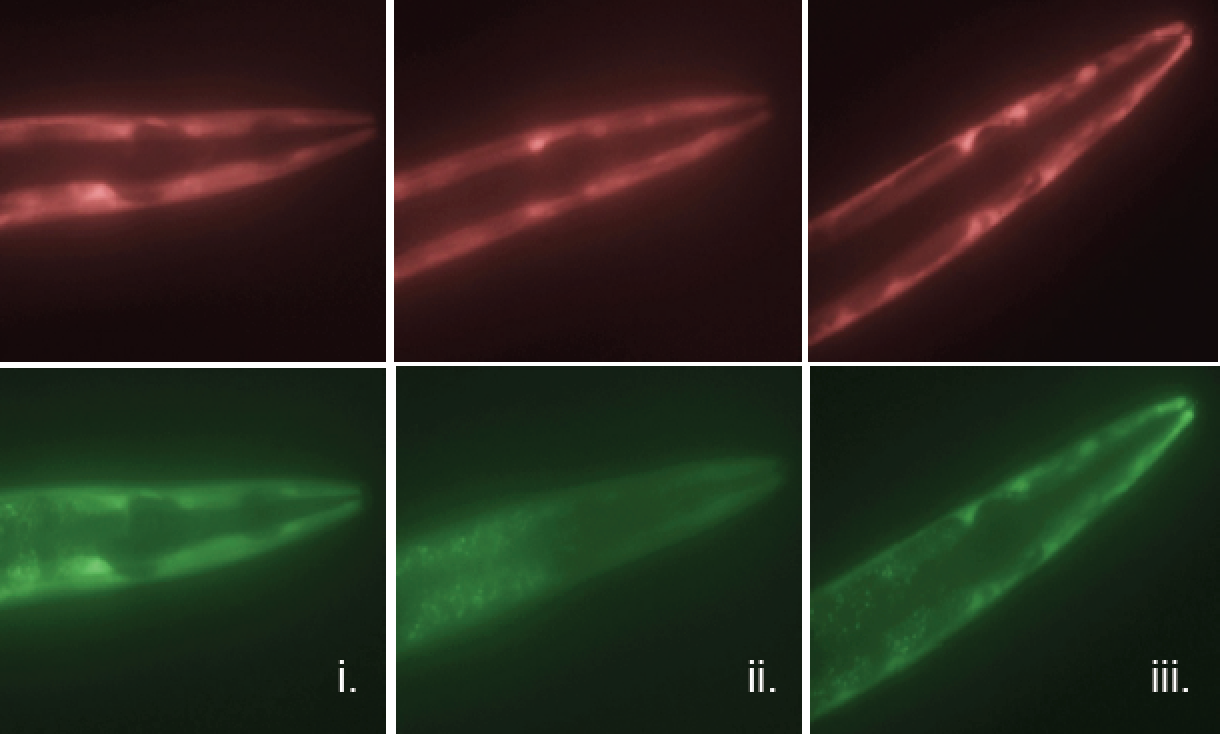

The researchers used a clever means to determine which genes were successfully translated into protein and which fell under regulatory control and were halted in the mRNA stage. To do this, genes in C. elegans were fluorescently labeled in such a way that translation or non-translation could be seen by a color change. Those genes that were merely transcribed into mRNA glowed red while those successfully translated into protein glowed green, (see accompanying image).

Technicolor genes: Here, genes of the nematode worm C. elegans have been fluorescently labeled. Those genes that are transcribed into mRNA but fail to become protein (due to regulation by 3’ UTRs) are seen in red (top), while those that evade 3’ UTR regulation appear in green (bottom).

The study demonstrated that the regulation of genes by 3’ UTRs of varying length occurred in a tissue-specific manner. In muscle tissue, for example, mRNAs bearing shorter 3’ UTR transcripts apparently evaded regulation by microRNA and were successfully translated. Further experiments demonstrated that where this process was blocked, mRNAs failed to be translated into protein, thereby compromising muscle tissue, with resultant muscle paralysis observed in the worms.

Research into the mysteries of the 3’ UTR region continue and are expected to have broad implications in a variety of human diseases.

More Science and technology

ASU researchers engineer product that minimizes pavement damage in extreme weather

Arizona State University researchers have developed a product that prevents asphalt from softening in extreme heat and becoming…

New study finds the American dream is dying in big cities

Cities have long been celebrated as places of economic growth and social mobility, but new research suggests that their role in…

Ancient sea creatures offer fresh insights into cancer

Sponges are among the oldest animals on Earth, dating back at least 600 million years. Comprising thousands of species, some with…