"Westworld" — the hit HBO show about a technologically advanced, Western-themed amusement park involving synthetic androids — riffs on questions about humanity, artificial intelligence and science.

The robot saloon women and gunfighters in the park exhibit intelligent behavior indistinguishable from a human.

Is anything like the tech in the show in the pipeline? Are roboticists thinking about the issues raised by creating something that looks exactly like a human? Should we make something as smart as ourselves?

To find out, we talked to Heni Ben Amor, a roboticist at Arizona State University and an assistant professor in the School of Computing, Informatics, and Decision Systems Engineering. Ben Amor’s research focuses on artificial intelligence, machine learning, human-robot interaction, robot vision and automatic motor skill acquisition.

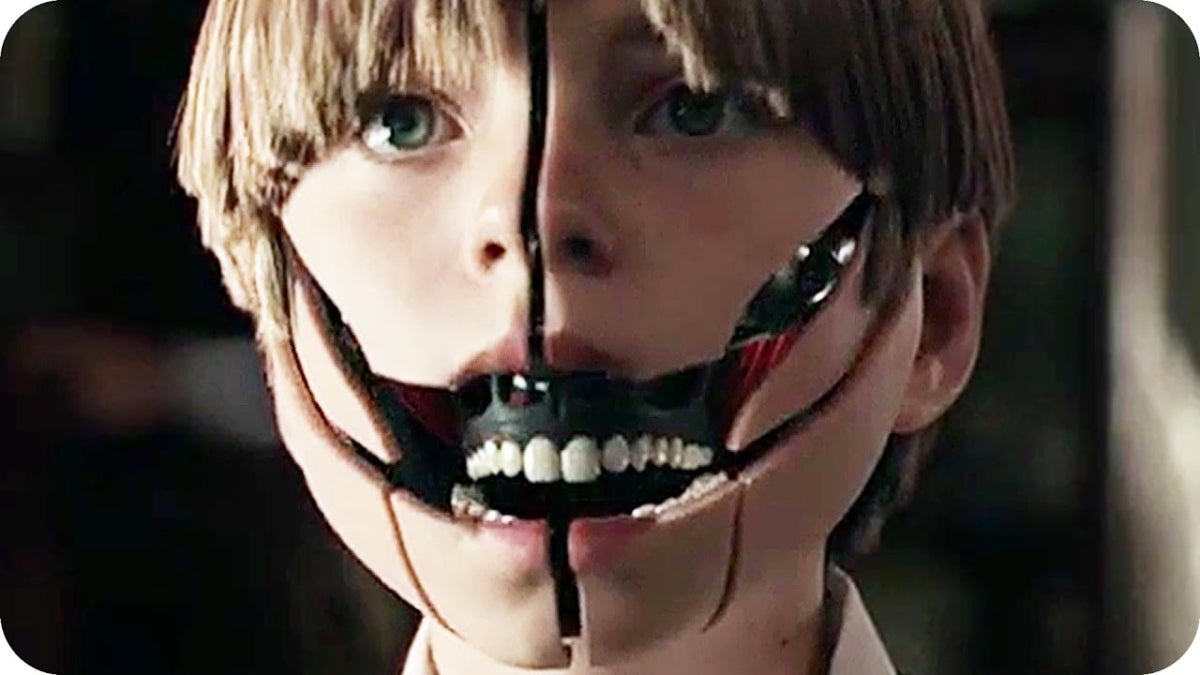

Which is a woman and which is an android? (Answer at the end.)

Photo courtesy Heni Ben Amor.

Question: What are your initial thoughts about the show?

Answer: Personally I think it follows the typical trend in Hollywood to have a bleak outlook on what’s going to happen and how robotics is going to influence our society. In other countries, for example Japan, depictions of robots are more positive and have a slightly different attitude. Still, as a fan, I appreciate their artistic value.

Q: How far are we from creating what you see in the show?

A: Very far away. I think there are some underlying assumptions that are too far away from what we have at the moment. One of the things depicted there are sentient robots, robots that actually have a very good idea of what they are and what the environment is and what the emotional state of a human partner is. All of these things are not tackled by robotics at the moment. We are too far away from that, especially this aspect of having sentient robots with self-awareness and a goal or a mission that is their own. … I think the current state of the art is the animatronics you see at Disneyworld, puppets that look fairly humanlike. They impress you the first couple of seconds, but it’s typically within seconds you lose this impression of having a real person in front of you. There is also no intelligence in the sense that these animatronics would stray too far away from the script.

Q: Can a machine act intelligently? Can it solve any problem a person can solve?

A: Definitely. Machines can solve problems humans cannot solve. For example, take the Rubik’s Cube, which for a long time was seen as a tricky task only smart people with dexterity and motor skills can solve. Nowadays robots are much better than humans at that. They can solve it in seconds. Recently I read a report where a robot solved it in a second. There are some tasks where robots can achieve super-human results, but I think what is so unique about human beings is that they are so adaptive and versatile. … We can do many, many things, and survive in a changing and challenging environment. Robots today typically can only perform a single task very well, even better than a human. But they are not able to transfer the knowledge on to new tasks or new environments.”

Q: What are your thoughts on creating an android of a relative, like a deceased grandparent or a child?

A: This of course is a very loaded question. I was working with a professor in Japan who created copies of himself and his daughter. These robots look very humanlike. Appearance-wise there is a quite a lot of progress we have done in the field, but again it’s a question of convincing results in behavior. This immediately brings the question of robotics and ethics to the surface. This is not something to take lightly and the community isn’t taking it lightly. There is an entire technical committee in the Society for Robotics and Autonomous Systems that is looking at the ethics of robotics. … There is an entire universe of ethical questions out there that need to be addressed. It’s not only the robotics community that has to think about that. It combines people from psychology, law — what does law tell us? What is the right decision from a legal point of view? At the moment I think the question of bringing deceased people back to life is too far away, it’s too Hollywood. You would not bring back the soul of that person.

Japanese roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro created a copy of himself. Photo courtesy Heni Ben Amor.

Q: How would you feel if you found out that someone you were working with is a robot?

A: The question is: Does it make a difference? Ultimately, I think the way we perceive the world is through the behavior of a person … We think, ‘Today he is nice.’ We try to figure out what is his internal mental status, and that is how we perceive other people. Ultimately, if a device is convincing enough to make me simulate its internal state, then I don’t really care whether it’s human or robot.

Q: But you would want to know ahead of time?

A: I’m completely indifferent. I think this is also the case for many people. Many people have watched an animation show. In animation, all of what you see if fake. It’s not true. What the word “animation” stands for is “life.” It does not stand for movement. … The idea is to create this illusion of life, and people get attached to something that does not exist. Many people have cried at the end of an animated movie. … Any artificial system is too far away from our human capabilities at the moment. People may be impressed by what you see on TV, but it’s not much different than these animated characters to which you get attached. If you get attached to it, it doesn’t really matter whether it’s an animated character or a robot or it’s human. Believing these robots could get a soul and become conscious and sentient, that part is horrible, and we are not there. But if a robot does something funny, I’ll laugh at it. I don’t care whether it’s a robot or not.

Q: One thing that strikes me in talking with you is that when you study robotics, you’re studying humans in a way.

A: We are very much inspired by biomechanics in order to figure out how humans manipulate the world, how we walk in the world. It’s very similar to how aerospace engineers study birds in order to get inspiration and basic principles. Once you have those basic principles, you can create an engineered solution and follow the same approach. … Similar to that, we as roboticists look at humans in order to get inspiration about modularity. A human being is not one big piece; it’s not this monolithic thing. There are millions of pieces inside that work together in synchrony. Creating synchrony among millions of pieces is actually really tricky. Even the smallest mistake can completely offset the system and make it fail. Despite that, we human beings seem to work perfectly. If you look at the billions of neurons in your brain, they work in synchrony. They also work with the muscles. It’s also about the physical composition of our bodies and why our muscles are created in a specific way and how that is shaped by the environment. ... If I need a robot for a manufacturing environment, then its appearance and behavior needs to be completely different from a robot that roams around the desert to find water. We definitely study a lot of biomechanics and how human cognition works.

Top photo: Courtesy of HBO

Answer: The one on the left is an android created by Japanese roboticist Hiroshi Ishiguro.

More Science and technology

Ancient sea creatures offer fresh insights into cancer

Sponges are among the oldest animals on Earth, dating back at least 600 million years. Comprising thousands of species, some with lifespans of up to 10,000 years, they are a biological enigma.…

When is a tomato more than a tomato? Crow guides class to a wider view of technology

How is a tomato a type of technology?Arizona State University President Michael Crow stood in front of a classroom full of students, holding up a tomato.“This object does not exist in nature,” he…

Student exploring how AI can assist people with vision loss

Partial vision loss can make life challenging for more than 6 million Americans. People with visual disabilities that can’t be remedied with glasses or contacts can sometimes struggle to safely…