Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. To read more top stories from 2016, click here.

Plenty of robots can shoot hoops. It wouldn’t be news that an Arizona State University robotics expert created a robot that can sink a basketball.

What’s new is that the robot taught itself to shoot a basketball in a matter of hours, something it would take even an expert programmer days to accomplish.

“If you think about it, the human would first have to learn how to” program robot behavior, said Heni Ben Amor. “You’d have to go through a master’s and PhD program. If you take all of that into account, it’s years. If you’re an expert, it’d be a couple of days, maybe a week.”

Ben Amor is an assistant professor in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering's School of Computing, Informatics, and Decision Systems Engineering, where he leads the ASU Interactive Robotics Laboratory.

He and his team built a robot dubbed Sun Devil with a pair of arms.

“We pose the task to a robot, and through trial and error the robot learns the task on its own, ideally in a limited amount for time,” Ben Amor said. “You go for lunch, and by the time you come back, it’s done.”

He meant that literally. They plugged the algorithms into two robots. One learned in two hours, the other in three.

“For our group this was a milestone,” Ben Amor said.

Robots have wear and tear. They break. The goal here was to have a robot that can learn very quickly and program itself. If robots can program themselves, humans wouldn’t have to do it. It’s a skill that generally requires a doctorate in robotics and computer science.

Sun Devil started from scratch. It didn’t have any kind of idea what kind of movement would allow it to get the ball into the hoop. The only requirement Ben Amor’s group gave it was the ball should be in the center of the hoop.

The robot tried out different movements in the beginning, some of which weren’t dynamic. Bit by bit it figured out how to improve its movements to get the ball closer and closer to the hoop. Automatically, it discovered that sinking the ball actually required a dynamic motion, and it discovered that motion.

The key was that the robot did all of this as quickly as possible, with a minimum of trials.

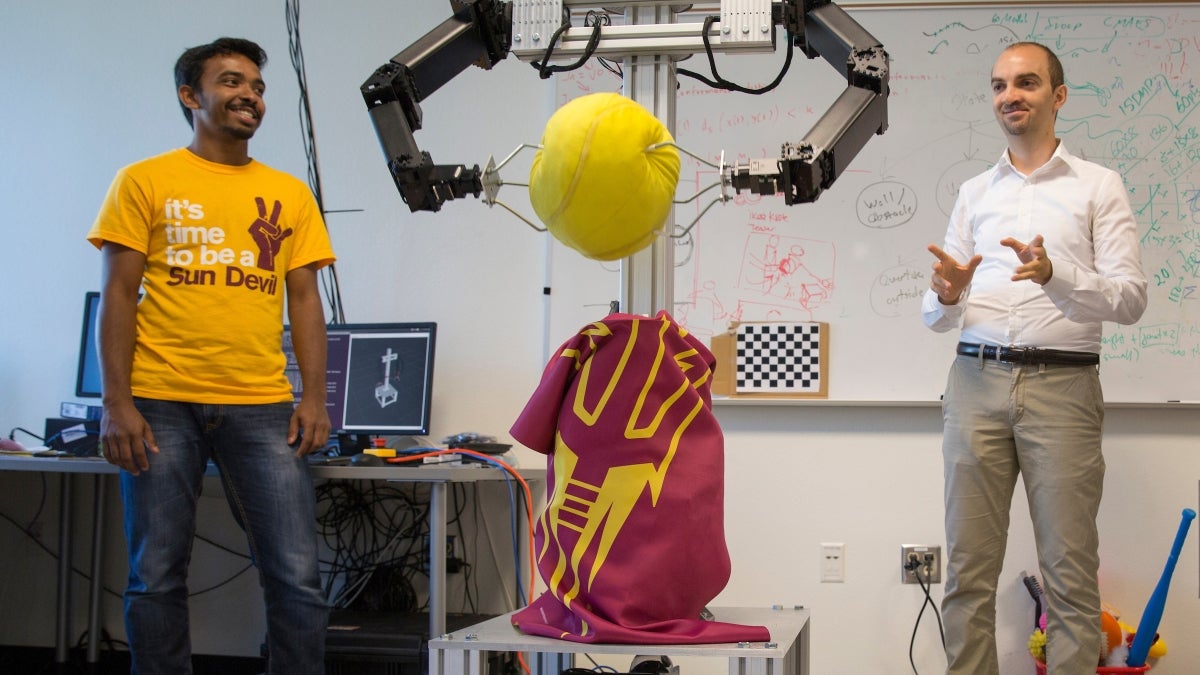

ASU assistant professor Heni Ben Amor's robot, called Sun Devil, taught itself to shoot hoops in a matter of hours. It also taught itself an algorithm for explosive movement. Photo by Jessica Hockreiter/Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering

“A lot of machine learning algorithms, many of these algorithms requires hundreds of thousands of trials before you actually learn something,” Ben Amor said. “If you wanted to optimize a robot car, you would have to drive it around and do crash tests for hundreds of thousands of hours before it learned something. That, of course, is not really helpful.”

It would take a team of scientists creating equations and models to program a dynamic motion to sink a basketball. Using two arms makes the task even more complicated.

“If you have two arms, it becomes a much more challenging task because these arms have to be synchronized in time in order to make sure the ball doesn’t drop out of the hand of the robot,” Ben Amor said.

The new algorithm created by Ben Amor’s group does this very quickly.

“It systematically tries out different parts of the search space, so different possible potential solutions,” he said. “Systematically, it tries to figure out what is the most likely part of the search space where my solution is. It’s an informed way of guessing or estimating where the solution is.”

And the result is nothing but net.

Top photo: ASU assistant professor Heni Ben Amor (right) has created a robot that can shoot a basketball after programming itself in a matter of hours. Computer science graduate student Yash Rathore helped show off the technology. Photo by Jessica Hockreiter/ Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering

More Science and technology

New study finds the American dream is dying in big cities

Cities have long been celebrated as places of economic growth and social mobility, but new research suggests that their role in fostering opportunity has changed dramatically…

Ancient sea creatures offer fresh insights into cancer

Sponges are among the oldest animals on Earth, dating back at least 600 million years. Comprising thousands of species, some with lifespans of up to 10,000 years, they are a biological enigma.…

When is a tomato more than a tomato? Crow guides class to a wider view of technology

How is a tomato a type of technology?Arizona State University President Michael Crow stood in front of a classroom full of students, holding up a tomato.“This object does not exist in nature,” he…