Blazing a trail in engineering education

Annabel White is a junior earning a degree in electrical engineering from Arizona State University. She is a full-time student who has a part-time job at NASA.

But NASA doesn’t have any facilities in the Phoenix area. They do in Virginia, and that’s the reason White lives there.

So how is she earning a degree in a lab-intensive program like electrical engineering from across the country?

Three words: Web-delivered education.

Just don’t call it an online class.

ASU’s undergraduate degree in electrical engineering is the first such accredited program that is completely Web-based. Enrollment is set to eclipse the traditional program, and demand is surpassing expectations.

“Overall this has been a really good program for me,” White said. “It’s allowed me to do exactly what I’ve wanted without having to relocate.”

Lab work is done through kits at home. For instance, in the introductory circuits course students buy a kit that implements a suite of instruments on their laptops functionally similar to the instruments in a traditional physical lab. It also has a proto-board, where they assemble physical circuits just like on-campus students do.

“This approach has been so successful that some of our resident students are requesting to do the labs at home rather than coming to a scheduled lab session,” said professor Marco Saraniti of the School of Electrical, Computer and Energy Engineering, part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering.

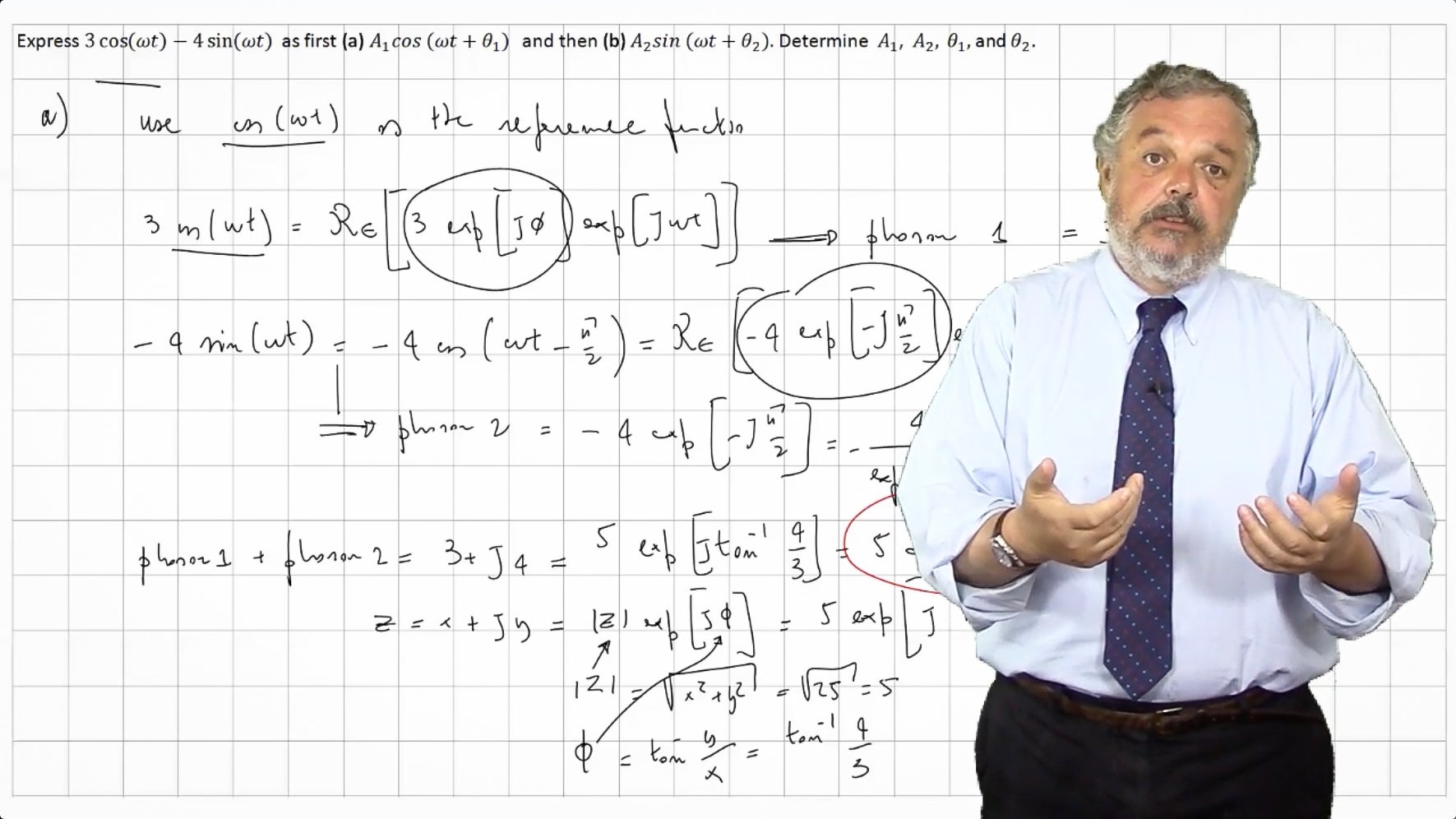

Professor Marco Saraniti uses a display tablet to write problems for students taking his Web-based electrical engineering courses.

Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Saraniti, director of Web-delivered education in the school, developed the program with school director Stephen Phillips.

“We don’t have two programs; we have one,” said Saraniti. While the delivery system is different, there is only one accreditation. “They are engineers certified by ASU like anyone else,” he said.

White likes the convenience and flexibility of not having to go to lectures. She chose the ASU program because it was the only accredited degree available.

“They’ve really made it enjoyable,” she said. “I think one of the biggest differences is how extensively the courses are developed. Some online classes just give you a book and it’s like an independent-study kind of thing. But this class with the pre-recorded lectures, it’s a lot more like being in a campus class than any other classes I’ve taken.”

Rather than using technology to mimic on-campus classes, Phillips and Saraniti designed the classes around the technology. Doing the former wasn’t going to produce what they wanted to create.

“If you try to do this, you will have a sub-par product,” Saraniti said. “This is an approach completely different from what everyone else is doing.”

For classes, Saraniti uses video-conferencing software that can accommodate up to 20 people. “I will have a screen with 20 little faces, and everyone can see me and talk to me,” he said.

To describe an equation, Saraniti shares the screen of the tablet with the students, who can see in real time what the professor sees and writes on the screen with a stylus. At the end of the session, the handwritten electronic pages are saved in a PDF file that is transferred to the student. It’s like taking the blackboard home. During the whole session, both student and instructor can see and talk to each other.

It works, White said.

“You can tell the amount of time and effort they’ve made developing these visual environments so we get the same experience the on-campus students do,” said White (pictured left). “You get the same kind of engagement you do on campus.”

The 120-credit-hour degree program includes core-engineering courses and a minimum of 45 upper-division credit hours in specialty courses — including such topics as analog and digital circuits, electromagnetic fields, microprocessors, communications networks, solid-state electronics and electric power and energy systems.

White said the labs are “really great. That’s a question a lot of people ask. … The instructors have done a really good job of designing lab work to do.”

The school has just received a grant to buy a remotely controllable electron microscope. Remote students will first watch videos explaining the theory and practice of electron microscopy. They’ll buy an inexpensive kit of chemicals that will allow them to produce samples with suspensions of different nanoparticles. The samples will be mailed to an ASU lab, where a teaching or lab assistant will physically load the samples in the microscope. The student will then remotely control the microscope, in real time, through a Web interface, and see the nanoparticles they produced.

Matthew Pierce is a junior who attends classes on the Tempe campus. Saraniti’s class was his first experience with Web-based education.

“I’m a more traditional student, and I was a little worried about it, but Professor Saraniti’s way of doing the online videos helps me understand how to do the examples,” Pierce said. “Professor Saraniti goes through example problems and goes through the steps to solve those problems. It’s just like being in class, but he goes through a lot more examples than he would in lecture. … Online you do it at your pace, so he can provide additional videos. In class he just has to cover the main portion of the material, so a lot of derivations don’t get shown.”

In his online videos, electrical engineering professor Marco Saraniti introduces the lesson on the side, such as in this example, and then fills the screen with the lesson material. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Like Pierce, students have told Saraniti that they like the fact they can rewind and rewatch sessions. “This is what they like,” Saraniti said. “They can repeat it.”

During the fall semester, Pierce took Saraniti’s Fundamentals of Electromagnetics class. In the spring he will take another web-based class. “The way professor Saraniti does it, I like it,” Pierce said.

Students enrolled in the program tend to be older transfer students with some college experience. A significant percentage are veterans, and many others work full-time.

“We are serving a segment of the population that has been historically neglected by traditional higher-education institutions,” Phillips said. “You can see how an appropriate use of technology can be instrumental to providing access to knowledge to a broader audience of students than a traditional delivery.”

Cassandra Steeno is a junior attending classes on the Tempe campus. Some of her friends raved about the Fundamentals of Electromagnetics class on the Web.

“It was a lot better than some of the classes I’ve taken in person,” Steeno said. “It covered a lot more material. That’s important to me because that’s how I learn — bottom up.”

Steeno took an online class in high school and hated it. She said one of the biggest advantages of Saraniti’s class was the ability to Skype with him.

“It was exactly mimicking office hours, with face-to-face contact even though you’re not in the same room,” she said. “That was one of the best parts of taking his class.”

Face-to-face contact with professor Marco Saraniti over Skype is one of the reasons students praise his Web-based courses. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

This may be the wave of the future. Saraniti said the traditional approach to higher education is becoming unsustainable.

“The cost is skyrocketing, while the promise of improving the life of young people through knowledge is less and less certain,” he said. “A university is a place that does one thing in two steps: generating knowledge and transferring it to students. The traditional approach to this mission is getting progressively less effective and more expensive. This is the reason for the urgency.”